This is another “extra edition”, to keep you up to date on my reading project: the IVP Dictionary of the Old Testament Prophets. The short version is included in the title: from “Isaiah” to “Sin” in 360 pages. With about 200 pages left to go, I am on track to finish on time, two weeks from now.

Before I share a bit more on what I have read, I would like to backtrack a little and write about why I am doing this.

I am reading: Mark J. Boda & J. Gordon McConville (eds), Dictionary of the Old Testament Prophets (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2012).

In case you missed previous reports:

Launch Video (4 minutes) \ First Report \ Second Report

Reading as Foundation

Many years ago, during my first year on staff in the School of Biblical Studies (SBS), I did something similar. The year was 1990 (yes, I am that old). The location was Honolulu (I know, a tough place to be). The reading was part of my master’s degree in biblical studies through the University of the Nations.

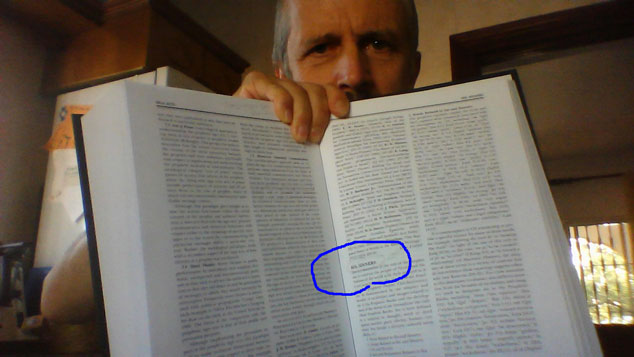

During my nine months of staffing this course I read through the entire Zondervan Pictorial Encyclopedia of the Bible, a five-volume work with over 5000 pages (I admit this includes the many pictures implied in “Pictorial”; the IVP dictionary includes none). In the months following, I continued to read a number of hefty volumes, mostly related to eschatology and the end times, in order to write my thesis.

I graduated in 1991 and moved to Germany in 1992 in order to start the SBS there. As it turned out, I did not find anyone to join me, so for that first school, I was the team. I did have guest speakers come in for about 9 of the 36 weeks, but the rest of the course was mine to teach. All the teaching was in German, a language I had learned in school, but in which I had not done any teaching before.

Besides the grace of God, the only reason I managed to pull this off is precisely the reading I had done during the 2 ½ years before I moved to Germany. I was loaded. I had taken in so much biblical studies, background information, introductions to all the books of the Bible, and larger theological themes connecting all the various bits and pieces, that I was able to churn out lecture after lecture. And answer questions. I did not have time to study or to prepare very much, but in a sense, my reading had been my lecture preparation without me knowing it at the time.

So this kind of reading enabled me to survive that first year of leading a school, and what I picked up during my time in Hawaii has continued to serve me well ever after. It was a crucial foundation stone for the ministry I have been involved in.

Still sceptical? I recommend a book by Ron Smith, Read to Lead: Seven Examples from History. Different from my dictionary, it makes for light (but inspiring) reading. And maybe it will whet your appetite for something heavier.

Back to the Reading Project

In this light, the present volume is a bit of a disappointment. As its subtitle points out, it is indeed a compendium of scholarship, which therefore covers all sorts of warped and by now discarded theories (as well as those that are still current and hopefully less warped; time will tell). This has its value, but it is not a great help for teaching the Bible in the community of faith, whether a YWAM school or a church. I get enough out of it to make this a worthwhile exercise, but I don’t expect it will have anywhere near the foundational value my earlier reading has had.

The articles I have enjoyed most in this dictionary are strictly speaking often not in the area of biblical studies. It is the ones dealing with new approaches, usually bringing the perspective of another discipline or field of study to the Bible. This includes psychology and other social sciences, as well as for instance rhetorical criticism (the study of how an author or a text seeks to persuade its audience). Another interesting new approach is the study of intertextuality: how does a text respond to, reuse and recycle, build on, and even dialogue with other texts?

These articles give a good feel for recent developments and provide a peek into where biblical studies has been going. However, they do not offer much help in interpreting passages, since they are general introductions to these various subjects. From the article on “Prophecy and Psychology” (610-23), to give an example, I learned more about psychology than about biblical studies.

Since I am on the subject, though, I do not want to withhold this quote from “Prophecy and Psychology”:

E. C. Broome later argued (1946) that the cumulative effect of the data – especially the claim that Ezekiel was mute for seven years (Ezek 3:22-27; 24:25-27; 33:21-22) and the notice that he laid for 390 days on his left side and then forty days on his right side (Ezek 4:4-6) – indicated that this prophet was a paranoid schizophrenic, with periods of catatonia, hallucinations, delusions of persecution and grandeur, narcissistic-masochistic conflict and withdrawal/anxiety (…) For Broome, Ezekiel was “a true psychotic,” though this was unrecognized in Ezekiel’s day and he was merely seen as an ecstatic. (Ibid., 615)

I hasten to add that the article is critical of this view and considers it an example of what it calls “Old Psychology”. On the next page it states, and I am sure you will be relieved to hear:

K. G. Friebel makes the case that they are intentionally chosen non-verbal behaviors designed to communicate specific messages to an audience. They are thus evidence not of the prophets’ abnormality, but rather of the high skill as communicators and rhetors.

So either Ezekiel is a raving lunatic or a brilliant communicator – your pick.

Gems and Highlights

I have realised it is not easy to write a report on my reading, for an obvious reason. This is a dictionary and therefore each entry is independent from all the others. There is no developing plot or progression of ideas; there is merely an alphabetical order.

I could point out how fitting it is to span an arc from Isaiah to sin (see title). Or I could quip that it would actually make more sense to go the other way: from sin to Isaiah (since Isaiah presenta the solution of the problem of sin). But the fact is, of course, that the beginning and end point for this report is entirely random. I just happened to start the four weeks with Isaiah and end with sin.

The best I can do is to share a few of the highlights I ran into – in alphabetical order! So here we go.

“Israel” (391-7)

You are probably aware of this, but in the Old Testament it is not always easy to determine who exactly is meant with Israel. After Solomon’s death his kingdom split into two parts. The ten tribes in the north were often referred to as the kingdom of Israel, whereas Judah and Benjamin became the kingdom of Judah. So in the prophets Israel often – but by no means always – refers to the northern kingdom.

This article claims that in the phrase “God of Israel”, Israel always refers to the whole nation. I have not checked it, but it would make sense. He is never the God of only some tribes, and certainly not the God of the northern kingdom. By the way, apart from Ezekiel, the prophets rarely use Israel as a name for the land. They put a strong emphasis on Israel as the people, not the land. Just saying.

One more gem from this article. A number of times Isaiah refers to both Jacob and Israel in the same verse (e.g. Is. 40:27; 43:1; 44:21; 46:3; 48:1). The article links this with the Jacob narrative in Genesis (395). Jacob becomes Israel. The change in name of course marked an inner transformation, but it was an incomplete one; in Genesis Jacob/Israel continued to be a work in process. The same could be said of Israel as the house of Jacob. When God promised salvation through Isaiah, he was quite realistic as to what he was getting into; Jacob doesn’t easily morph into Israel.

“Israelite History” (397-422)

With approximately 25 pages this is the longest article in the dictionary. I don’t like it very much (it is quite reluctant to treat biblical text as a source of historical data), but it did contain this little informational gem: 85% of settlements in the hill country (the region between the central mountains and the coastal plain) were abandoned and not re-occupied after 700 BC (408). This provides a graphic illustration for the severe devastation that the Assyrian invasion wrought during Isaiah’s lifetime (as described by the prophet in for instance Is. 1:7-9).

“Jeremiah: Book of” (423-41)

I already mentioned this in the previous reading report, but the book of Jeremiah is the one prophetic book for which we do have two rather different versions, represented by the Greek Septuagint and the Hebrew Masoretic text (the text used for most Bible translations). The Masoretic text is about 12% longer and has the oracles against the nations at the end, not in the middle of the book.

Fact is, the structure of Jeremiah is difficult to define or explain. One way to look at it is that there is a double structure, 1-25 and 26-45. The first part mostly consists of Jeremiah’s prophecies and his personal laments or complaints. The second half includes mostly narratives. This original structure has been changed by later insertions. Some of this added material sits uneasy in its present position.

It appears that quite a bit of the extra material in the Masoretic text consists of introductions and concluding remarks and other formulae, so material of relatively secondary importance. This is a far cry from the idea that the scribes added substantial amounts of newly created content of their own making.

Might this suggest that the postexilic scribes were not so much striving for literary creation and a polished final product? What if instead they were attempting to preserve whatever was available to them of Jeremiah’s work? How come that the book of Isaiah is such an incredibly refined and polished unified whole, whereas Jeremiah is full of rough edges and illogical sequences (jumping back and forth in time)?

It is interesting to speculate on such questions, but I am afraid there are no firm answers.

“Jeremiah: History of Interpretation” (441-9)

This article contains a noteworthy statement on the structure of Jeremiah, which fits well with what I wrote in the previous segment: “The structure of the book as a whole remains a topic under discussion among interpreters, and no consensus as yet developed to account for it” (445).

“Joel, Book of” (449-55)

Joel 3:10 or 4:10, depending on your version, contains the call to beat ploughshares into swords. This is the exact opposite of Isaiah 2:4. The author of this article argues that the version in Joel is the original, used as a call to war, perhaps even an established expression even before Joel. “It appears that Isaiah and Micah reverse this common idiom in order to illustrate the peacefulness of the eschatological age. Joel, by contrast, seems to preserve the original idiom” (451).

Makes sense. People are more likely to issue a call to war than a call to peace. The idea to convert a ploughshare into a weapon probably comes quicker than thinking the other way around.

“Prophets in the New Testament” (650-7)

This article includes statistics on quotations from the prophets in the New Testament (650). There are direct quotes from Isaiah in 65 verses. Next are Jeremiah, Hosea and Zechariah, with 6 verses each, and Joel and Amos with 5 verses.

Allusions and parallels are more numerous and spread out more equally. Isaiah still leads with 210. Ezekiel has 130, Jeremiah 95, Daniel 70. Daniel is far shorter than the other three, so in proportion to its size, Daniel leads, although many of the allusions are in one book, the Revelation. Clearly then, Isaiah is the king of the prophets.

But it did I really need to read 900 pages to figure that out?

Read the next issue on this Special Project: the final report!

Disclosure of Material Connection: Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission.