Paul’s epistle to the Romans is a book I taught quite a bit during my early years in the School of Biblical Studies, but not much at all in later years. In the course of a school one cannot, alas!, teach every great book in the Bible oneself; other staff want their share of teaching, and even the most passionate teacher at some point runs out of energy. (For those intermediate years I had to make do with book likes Revelation and Isaiah; not bad either.)

Over the past few years, however, I have been asked several times to teach Romans. My relative absence during the years in between enabled me to take a fresh look once I started to prepare for these lectures, which turned into some valuable gains and the fresh understanding to be shared below.

You can also watch this content as a VIDEO PODCAST

Subject

So: in this issue of Create a Learning Site I share new insight I have gained into Romans 1-8, with a special focus on Chapter 7 and the poor “wretched man” Paul refers to there. This new look (not perspective; this is not about the so-called “New Perspective” on Paul) at Romans really helps to make sense of what Paul is doing in these chapters.

Before I continue, I should give credit to Ben Witherington’s commentary on Romans (1), since quite a bit of what follows was triggered by this book. However, it has been some years since I read it; this is very much my own version of his ideas. So don’t write an angry e-mail to poor Mr. Witherington if you don’t like what you read here; it is not his fault.

A Classic Structure of Romans 1-8

A fairly standard way of looking at Romans 1-8 is as follows:

- Introduction to the letter (Rom. 1:1-17)

- All have sinned: the human problem (Rom. 1:18-3:20)

- Justification by faith: the solution, with Abraham as illustration (Rom. 3:21-4:25)

- Chapter 5… ???

- Sanctification: delivered from sin (Rom. 6)

- Sanctification: delivered from the law (Rom. 7)

- Sanctification: by the Spirit (Rom. 8:1-17)

- Glorification (Rom. 8:18-39)

Chapter 5 sits a bit uneasy in this structure: Is it about reconciliation as distinct from justification? Does the Adam passage repeat some of the same material from a different perspective? Does Paul want to broaden the scope by moving from Abraham to Adam (thus placing the people of Israel into the same troubled boat as the rest of humanity? How do the two halves of the chapter fit together??? Is Paul rambling in this chapter, as some preachers do, until he figures out (in Chapter 6) where he wants to go with his argument? By no means! (as we will see).

Besides defining the structure of the book as moving from problem to solution, it is also very much a topical perspective. It virtually reduces these chapters to a systematic theology by Paul: this is his soteriology, a systematic theologian might say, that is, Paul’s understanding of salvation (from the Greek word sōtēria, salvation).

The problem with this structure is not that it is wrong, but that it leaves so much out; that is why I used the word “reduces”. It removes the historical flesh and bones of the biblical story, leaving us with a handful of fairly abstract ideas. This is certainly not how Paul starts off in Romans 1:2-3 (“promised beforehand through his prophets in the holy Scriptures, concerning his Son, who was descended from David according to the flesh”; ESV). Neither does it do justice to how he continues.

A Different Structure for Romans 1-8

Another, more positive feature of the structure above is that it lets Romans 1-8 end with a resounding climax in the second half of Chapter 8. But it is not the only such climax in these chapters. There is an earlier one in the first half of Chapter 5. Let’s take it as a possible cue that these chapters should actually be divided into two parallel parts, each ending with a climax, and see where that takes us:

- Introduction to the letter (Rom. 1:1-17 )

- Part 1 (Rom. 1:18-5:11)

- All have sinned: the human problem and how Israel failed to solve it (Rom. 1:18-3:20)

- How the promise to and through Abraham has been fulfilled: the solution (Rom. 3:21-4:25)

- The first climax (Rom. 5:1-11)

- Part 2 (Rom. 5:12-8:39)

- We are all in Adam: the human problem (Rom. 5:12-21)

- Crucified and raised with Christ: the solution (Rom. 6)

- Israel under the law: how Israel (and morality) failed to solve the problem (Rom. 7)

- Life in the Spirit: the solution (Rom. 8:1-17)

- The second climax (Rom. 8:18-39)

Notice that this structure splits Chapter 5 into two units, so that we no longer have two awkward halves that do not fit together. In addition, it makes it look like Paul covered the same ground (define the problem, then present the solution) twice.

Really?

But do we really have two parallel climaxes in these chapters? You may want to pause here to read and compare Romans 5:1-11 with Romans 8:18-39 yourself (it is a worthwhile exercise), but here are the similarities I noticed:

- Both passages refer to glory and hope, and focus on the future (Rom. 5:3-5; Rom. 8:18, 20, 24-25)

- In doing this, both affirm the absolute security we have in or because of Christ (expressed by the “much more” in Rom. 5:9-10 and pretty much everything in Rom. 8:29-39)

- Both refer to present tribulations and suffering (Rom. 5:3; Rom. 8:18, 35)

- Both speak of perseverance; in light of the future glory, this is the necessary and logical response to tribulation (Rom. 5:3; Rom. 8:25)

- In both passages the Spirit is present, presumably to help in this (Rom. 5:5; Rom. 8:23, 26-27)

- In both passages the above has everything to do with the fact that Christ died for us (Rom. 5:6-10; Rom. 8:32)

- This, in turn, is because of God’s love (Rom. 5:5, 8; Rom. 8:39)

Taken together, this is too much to be a coincidence. Obviously, Paul wants us to understand that his argument comes in two parallel parts, covering the same ground twice, even if in different words and images. Why this second look and what differentiates it from the first?

In Adam, in Christ: The Underlying Framework of Romans 6-8

Foundational for the second part of Romans 1-8 is what Paul puts down in the final 10 verses of Chapter 5: the contrast between Adam and Christ. Even though Paul will not refer explicitly to Adam again, and even though he does not even use the phrase “in Adam” in Romans at all (it’s only in 1 Cor. 15:22), it is this contrast between “in Adam” and “in Christ” that shapes the remaining chapters of Part 2.

“In Adam” opens a new angle on the predicament for which the gospel is the solution: sin is not just an individual problem consisting of bad choices that we might solve by promising to make better choices from now on. Sin is a power that won’t let us go. Sin is a tyrant that has all of humanity in an iron-clad grip, leaving death as the only possible outcome.

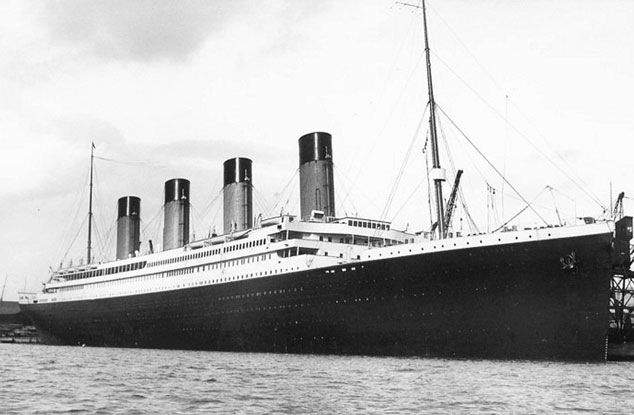

At this point, it is important to know that Paul is writing this letter to a group of house churches in Rome in which Jewish and Gentile believers are not getting along very well. Paul has more reasons to turn to Adam and our common humanity than theological interests. Paul’s aim in Romans is not only to present “his” gospel, it is also to restore mutual acceptance and appreciation between these two groups. To this end, he needs to confront both Jewish and Gentile pride. One way he does this is by pointing out they are both in the same boat, and this boat, “in Adam”, is a total shipwreck rapidly heading for the bottom of the sea: the original Titanic. (2)

Although this is relevant to both Jewish and Gentile readers in Rome, it does have one special application specifically for the first group. Crucial is not whether one is “in Abraham”; in fact, this is not a category at all. Decisive is whether one is in Adam or in Christ. By default, everyone, whether Jew or Gentile, is born in Adam. And if in Adam, then under the power of sin, without any prospect of escape. This is where Jews fare no better than Gentiles.

It explains why the remedy in Romans 6 needs to be so drastic. It is not enough that Christ died for us; we also need to die with him. This is the only way out. We have to exit the old humanity and enter the new humanity through death and resurrection as made visible in baptism.

Who Is Paul Talking about in Romans 7?

At this point, we are able to take a fresh look at Chapter 7, especially at the identity of the person speaking as “I” starting in verse 7. Quite a few different solutions have been proposed, too many to cover them all, but here are a few possibilities.

1. Paul as a Christian. Since Paul writes in the “I”-form, it would make sense to think he is speaking about himself. The question then becomes whether this is Paul before or after his conversion to Christ.

The latter interpretation, although widespread, can be excluded, because as early as Romans 7:6 Paul states (literally) we were released from the law (past tense). In Romans 8 Paul will explain in more detail how this works. But we already know the basic answer: out of Adam, into Christ; crucified and raised with him. So Chapter 7 and 8 continue the “in Adam” and “in Christ” framework established in chapter 5 and applied to sin in Chapter 6.

This is not to deny that a Christian may still struggle with sin, but this is simply not what Paul is writing about. So whoever Paul is speaking about, the experience is before Christ, not after (or in) Christ.

2. Paul before his conversion. Although Paul may have struggled with certain parts of the law in his pre-Christian life, it is not clear that he is referring to this here. Since Paul grew up with the law, there would not really have been a time when he was “without the law”, after which “the commandment came” (Rom. 7:9). And does this really match the picture we get of Paul elsewhere as a zealot for the law, apparently not suffering from any self-doubt worth mentioning?

3. Adam or humanity. For this reason, and because of the prominent place of Adam in chapter 5, others have thought that Paul is here identifying with Adam or perhaps with all of humanity. At least Adam was indeed without a commandment initially, and there are certainly some echoes of the Genesis story in this passage. Perhaps Paul starts off as Adam and from Romans 7:14 onwards voices a universal human experience. (3)

At the same time, the very commandment that Paul uses, “you shall not covet” (Rom. 7:7), does not fit the prohibition in Genesis 3. Besides, he refers to “the law” here and not only to one commandment. Therefore, although there are echoes of Adam in this chapter, he is not really the person speaking here.

4. The people of Israel under the law. For this reason, I think Paul has the people of Israel in mind (at least in verse 7-13) and speaks as a representative of the nation, an impersonation. In the context of Israel it makes sense that there was a time without the law; then the commandment came, at Mount Sinai. Even though this commandment was in and of itself an instrument of life, the presence of sin in Israel prevented it from having this effect. Instead, the commandment brought death.

There was one positive and useful outcome: it brought out into the open the very sinfulness of sin, its whole ugly face, leaving no illusion as to its true nature. It also demonstrated our inability as humanity to save – or improve – ourselves.

And this is where Adam comes in again: Paul describes the historical experience of Israel with the law as a replay of Adam’s fall, with sin playing the role of the serpent. Israel was supposed to be the solution to Adam’s sin, the agent to bring God’s salvation to the world, but ironically repeated Adam’s fall, since sin proved too strong and cunning an opponent.

Pagan Philosophers Knew This Too

It is difficult to decide whether from verse 14 on Paul is still impersonating Israel. More likely he has switched to speaking as a representative of the whole human race; the shift from past to present tense in verse 14 indicates something has changed. At this point, in the second half of Chapter 7, the Jewish dilemma does not differ much from that of the Gentiles, at least of those Gentiles who subscribe to higher standards of morality. Paul’s “I” is voicing a universal human experience. Pagan philosophers of Paul’s world had been aware of this. Some of their statements sound a lot like the dilemma Paul voices in Romans 7:

For the good that I will to do, I do not do; but the evil I will not to do that I practice. (Rom. 7:19, NKJV)

Desire persuades me one way, reason another. I see the better and approve it, but I follow the worse. (Ovid, Metamorphoses 7:22-21)

What I wish, I do not do, and what I do not wish, I do (Epictetus, Dissertationes 2.26.4)

As before, this leaves Jews and Gentiles in exactly the same boat: “O wretched man that I am! Who will deliver me from this body of death?” (Rom. 7:24, NKJV). Well, by now we know the answer.

This is where Paul’s exposition turns out to be eminently practical. Neither the law nor ethics suffice to turn us into better people. Effort isn’t wrong. But if we have tried and failed, try harder rarely is the solution. The road to moral improvement is not to try harder, but to reckon ourselves dead to sin and to live according to the Spirit.

Disclosure of Material Connection: Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission. If you purchase anything through such a link, you help me cover the cost of Create a Learning Site.

Literature

(1) Ben Witherington III, Paul’s Letter to the Romans: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2004)

(2) I hasten to add: God has brought, so to say, a second Titanic alongside the sinking one, and is not just saving individuals, but in a very real sense the ship itself. In the end, you may find those who would not accept rescue at the bottom of the sea, but the ship itself (the human project) will have been saved and transformed, sailing happily along in new, eternal waters, now truly indestructible and unsinkable. However, from a theological perspective, apart from Christ the human project after Adam was as doomed as the Titanic after it hit the iceberg.

(3) This is Ben Witherington’s view, as can be seen in this blog post. The second half presents his understanding of Romans 7: in Rom. 7:7-13 Adam speaks and in Rom. 7:14-25 (a representative of) humanity speaks.