According to Torsten, a good friend with whom I worked in the School of Biblical Studies for many years, this is the most important book in the Pentateuch. I disagree, of course. My wife thinks it is Numbers; for this reason I did an earlier issue giving six reasons to read Numbers. If you ask me, it might be Genesis or Exodus. Or could it be Deuteronomy?

You can also watch this content as a VIDEO PODCAST

At any rate, Torsten’s preference for Leviticus does show that it cannot be unimportant. And perhaps he has a point. I have to admit: this is the central book of the Pentateuch. And right in the centre of this central book, in Leviticus 16, we read about the Day of Atonement (or Purgation). In terms of vouchsafing Israel’s continuing relationship with Yahweh, this was the most important day of the year. And with this, we have already unearthed two reasons to read this book:

1. Leviticus is the centre (and heart) of the Torah. As Torsten points out, this book is of central importance in the Pentateuch and therefore foundational to the rest of the Bible.

2. In this book we read about the Day of Atonement. On this day, all ritual impurity and moral iniquity were removed from the sanctuary and the people. It would therefore be better to call this the Day of Purification or even the Day of Purgation, but Day of Atonement is the established term.

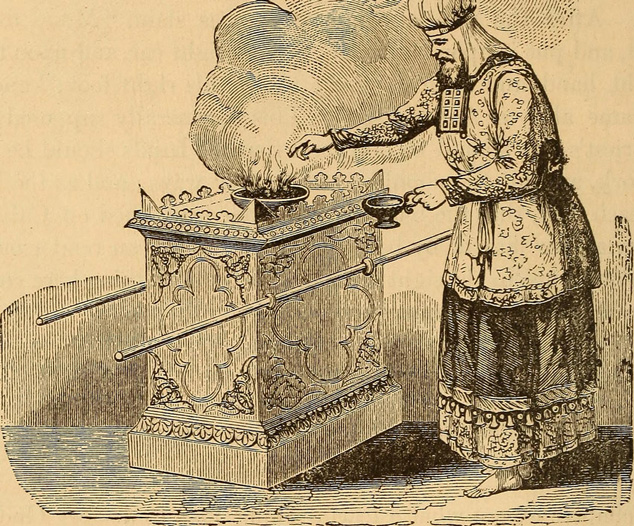

Together with the sacrificial system described in the first half of the book, this day dealt with Israel’s sin. As such, it prefigures the sacrificial death of Jesus in major ways (plural). At the same time, it helps us to understand how the sacrificial system worked. There was more to it than bringing an animal to take your place, to die in your stead, thus bringing out the seriousness of sin while also providing a way to deal with it. This was part of it, and the shedding of blood as a symbol of life functions as a powerful display.

There is another side to it, however, that is less known: by sprinkling blood the impurity and guilt were taken from the offerer and transferred to the altar. This is clearer in the Hebrew than in most English translations (so Gane 2004: 104). “So the priest shall make atonement for him for his sin, and he shall be forgiven” (Lev. 4:26b), the ESV reads, but it should say “atonement (or purification) from his sin”, not for his sin. The blood as the carrier of life transfers the sin from the offerer to the sanctuary and the altar, thereby removing it from the offerer. This is why the blood was not applied to the offerer: this would have returned his guilt and impurity back unto him (ibid.: 106)!

This leads to a problem. With time, more and more sin and uncleanness accumulate in the sanctuary. This problem is solved by the Day of Atonement (Lev. 16). Five animals are involved in the procedure: a bull as a sin offering for the priest, a goat as a sin offering for the people, a second goat for Azazel (sometimes translated as “scapegoat”, but more likely the name of a demon), and two rams for a burnt offering.

The first two animals are killed and some of their blood is brought into the Holy of Holies by the high priest, the only time in the year that anyone would enter there. It seems that this time, the direction of the transaction is reversed. Sin and impurity are not transferred from the one bringing the sacrifice to the sanctuary, but from the sanctuary to the corpses of bull and goat:

Thus he shall make atonement for the Holy Place, because of the uncleannesses of the people of Israel and because of their transgressions, all their sins. And so he shall do for the tent of meeting, which dwells with them in the midst of their uncleannesses. (Lev. 16:16)

Roy Gane’s (2004: 272) more literal translation clearly shows that the direction is one of removal away from the sanctuary:

Thus he shall purge [kipper] the [most] holy place from [privative min] the impurities of the Israelites and from their transgressions as well as all their sins…

Since both the bull and the goat are burnt outside of the camp, this goes quite a way toward solving the problem, but not yet far enough. The second goat is needed to deal more thoroughly with the moral transgressions of Israel. Through confession and the laying on of hands they are loaded onto this animal, which is then released into the wilderness, carrying its load of sins with it (Lev. 16:21f).

In other words, the sacrificial system described in the first half of Leviticus presents us with a two-stage process of dealing with impurity and sin, in some ways (an irreverent analogy, I admit) like having a large garbage container in front of the house that gets emptied once a week.

3. Leviticus helps us to learn the language of ritual. This is a language that people from the West, shaped by science and the Enlightenment, find difficult to understand. Ritual does not work through cause and effect in a physical or biological way. Instead, its essence is analogy, parallelism, and symbolism; its effectiveness derives from the operation of God and his spirit, not the operation of the laws of nature. In this way ritual enables connections on a deep level, conveying spiritual understanding and effects. It also provides a foundation of words and images and practices that make salvation intelligible.

4. Leviticus helps us to understand something foundational about God and about us as human beings. Since this comes through its teaching on ritual purity, separation, and “graduated holiness” (see below), this overlaps with the previous point. However, it is a significant theme in the book, so I have made it a separate item.

What we learn about God is that he is pure, holy, fearsome, and awe-inspiring. What we learn about ourselves is that we are not. The result is that we begin to fathom the immense gap that exists between humans and God; by nature, he is unapproachable.

When Nadab and Abihu ignore God’s instruction and do things differently, they are consumed by fire (Lev. 10). This is one of only two action narratives in the book (the rest is a narrative of instruction), which suggests it is an important demonstration of what the book is about. God cannot easily be approached; this requires careful thought and preparation – and caution! Granted, this is only half the truth about God, by far the smaller half (the other, larger half is his loving kindness), but it is an important half.

It shows in the graduated holiness, in which the dwelling place of God’s presence is clearly separated from the camp and is itself separated into three increasingly holy areas: the outer court, the Holy Place, and the Holy of Holies. The increasing value of the materials used (copper and silver on the outside, gold on the inside), underline this, as does the decreasing accessibility of these holy spaces: only ritually pure people could enter the court of the tabernacle, only priests could enter the tent itself, and only the high priest could enter the inner sanctuary, and this only once a year.

It also shows in the instructions for ritual purity and uncleanness (Lev. 11-15). These regulations are very much part of what makes this book so exotic, so not of our world. We may be able to sympathize with not eating rats or vultures, but what is the problem with some of the other animals? Why are they forbidden? And why do some of the other things such as menstruation or childbirth make someone unclean?

These questions have been extensively debated, and there may not be a consensus. What seems unlikely is that it is about health and hygiene. Too many items in these chapters cannot be explained this way, since they are not unhealthy. Some have argued that these things were unclean solely because God said so; according to them, there is no other rationale; it is all about obedience.

More likely in my opinion is that two factors are involved. One is that many unclean things are associated with death and mortality (this includes blood and even sexual intercourse and birth, which is the other side of mortality), and therefore should not be brought into contact with the immortal God and his sanctuary. The second factor is that of imperfection. This especially applies to those animals that don’t quite fit the ideal, such as: they chew the cud, but have undivided hooves, or vice versa (Lev.11:3-7).

Regardless of the actual logic involved, these instructions help us to start thinking in a different framework: pure and impure, holy and unholy – and God belongs to one, we come under the other of these paired options.

5. Leviticus teaches us about holy living; this is its central and dominating theme. Again, “holy” is not a category that comes naturally to us; it is not part of normal life (as the society around us understands “normal”). Its core meaning is separation, setting something apart for a specific purpose. When the word describes God, it also identifies him as the one who is entirely “other” or different.

At the same time, the word often takes on connotations of perfection, especially moral perfection. The “Holiness Code” in Leviticus 17-27 (especially Lev. 18-22) therefore includes many moral injunctions that continue to have validity. At the same time, these are mixed with others that are more difficult and ambiguous in terms of relevance and application. There is no easy answer. Just because a Do or a Don’t is in the book of Leviticus does not necessarily mean that we ought to practice it – or that we ought not to practice it!

Still, easy or not, these commandments are life-giving and worthy of reflection.

6. Leviticus teaches us about sacred time. It speaks not only of sacred space (the tabernacle and the Israelite camp), but also introduces sacred time. This is where the feasts and the Sabbath (Lev. 23) come in. The Sabbath proves that there is more to this life than work; in fact, there is more to this life than this life. The feasts combine a celebration of gratitude over God’s provision through creation (that is, the various harvests) with a commemoration of the exodus and desert wandering. They give meaning to time and reminded Israel (and remind us) of the higher purpose of life.

7. Leviticus shows us what God really wants. In the end, this whole setup with a tabernacle as separate, sacred space, regulations to keep Israel holy and ritually pure, and a sacrificial and priestly system to deal with error and transgressions (which would otherwise force God to terminate the relationship) are there so that he can dwell among human beings once again.

Here’s an idea. Maybe you still have your vacation ahead of you (and if not, surely there is a weekend coming up?). How about setting some time aside to read through the book of Leviticus?

References

Illustrations: The Pictorial Bible and Commentator: Presenting the great truths of God’s word in the most simple, pleasing, affectionate, and instructive manner (1878), 167 and 362. https://www.flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/14783943313/ and https://www.flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/14761839654/. No known copyright.

The Holy Bible: English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Standard Bible Society, 2001)

Roy E. Gane, NIV Application Commentary: Leviticus, Numbers (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2004)

Disclosure of Material Connection: Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission. If you purchase anything through such a link, you help me cover the cost of Create a Learning Site.