Every once in a while my Bible reading starts to run dry. I am not getting much out of it anymore. I catch myself thinking the same things as the last time I read a particular passage. Often, when I reach this point, I am in a rut, and it is simply time to change something. 27 years ago this was what led to me to do YWAM’s School of Biblical Studies (SBS). Boy, that and my masters in biblical studies gave me ammunition for years of productive personal Bible reading!

You can also watch this content as a VIDEO PODCAST

More recently, and less drastically, I read the Bible in Spanish, something I completed last year. It was slow going (my Spanish isn’t all that good), but reading a new version in a different language opened up a fresh encounter with Scripture. For me, it is often overfamiliarity with the text that holds me back from actually seeing and getting what it says.

I am at that point again. It is time for a change, and I will make it a special project. For this year, I would like to read the New Testament in Greek. Since it is a special project, I will be reporting on my progress, even if not through Create a Learning Site. More on this in a moment.

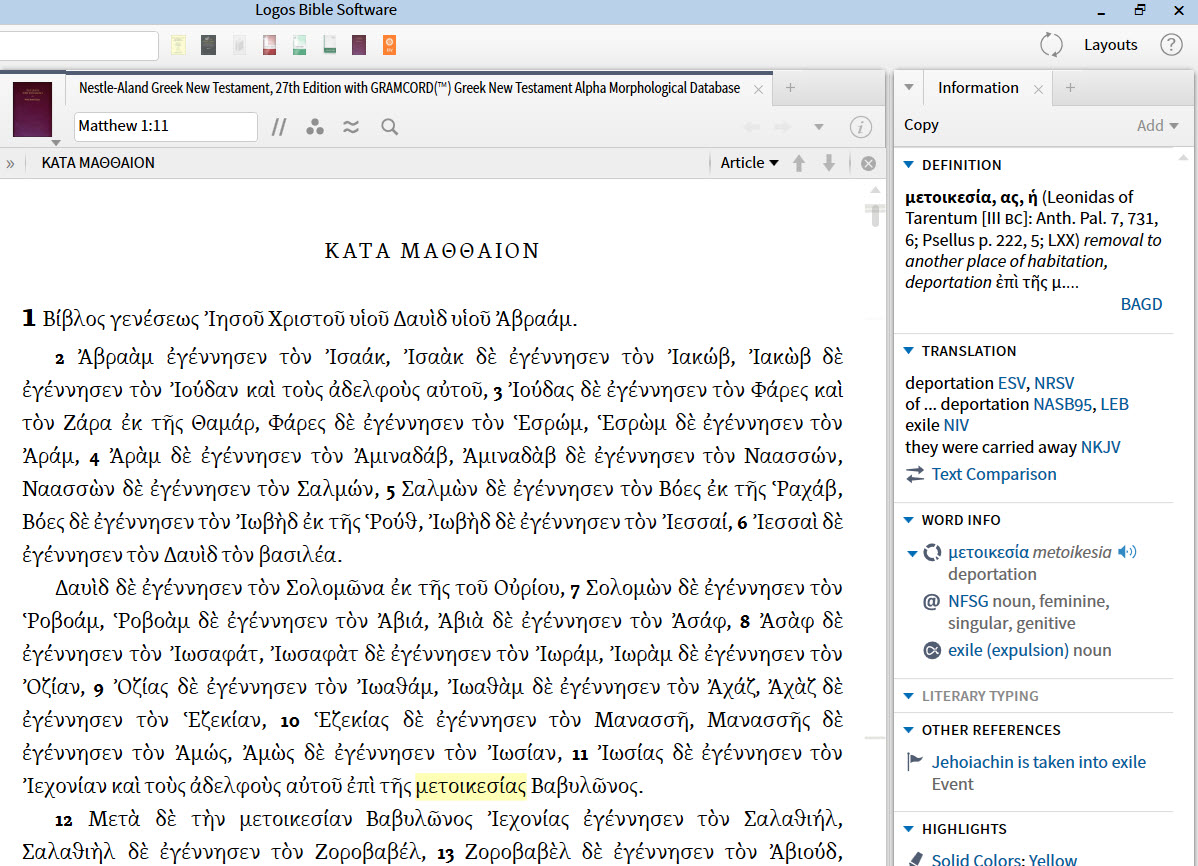

First, let me give you a brief sketch of my foundation in NT Greek and of the project. I did a three-month course (full-time) in NT Greek many years ago (1991). I have used Greek from time to time in Bible study and lecture preparation, but not nearly as much as I would like. In fact, I feel my grammar and vocabulary are a bit rusty, which is an additional reason I want to do this. I will be using Logos Bible study software, since it enables quick lookups for word meaning and also for information on the morphology of a word, that is, its form, inflection, and function in the sentence. Call it cheating if you will, but I would like to finish before the end of the year and not by the end of the decade.

Where Is This Happening?

I don’t want to post my updates for this special project on Create a Learning Site, and I am not planning to send e-mails on this either. Create a Learning Site will continue to be the place for longer and more substantial articles, so it can also function as a resource site, not cluttered by a large number of short entries.

Instead, I’d like to try out Tumblr. For one, this is a bit of a subversive platform-with-a-twist with not that much good Christian content on it (at least not in the area of biblical studies; I guess all the Christians are on Facebook). In addition, it allows me to have posts automatically shared on Facebook and Twitter as well, so people can choose the channel through which to follow my progress.

I have already done a trial run with the Gospel of Matthew, to find out if this is doable, and I quite liked the experience. Over the course of this month, will first publish a number of short entries based on this trial run. Afterward, I will continue with reading the Gospel of Mark. When I run into something interesting I will blog about it on Tumblr.

Pitfall 1: Aorist

Before I give you a foretaste of what I am heading into: I am aware of at least some of the pitfalls linked with reading and interpreting Greek. Multitudes of strange and questionable interpretations have been built with the help of “Greek magic”. It is amazing what you can do once you learn to dazzle your audience with the tricks of manipulating Greek words and verb tenses.

I will give just two examples here, albeit widespread and important ones. Much is sometimes made of a particular verb being an “aorist” as opposed to an “imperfect” or another form. The imperfect form of a verb often implies that an action had a duration or was repeated. In many cases this can be translated into English using the construction “he was… (walking, listening, etc.)”.

So does this mean that the aorist is punctiliar, in the sense that an action occurred only once or even once and for all? It is often interpreted this way, but this is emphatically not the case. Instead, the aorist form means the author or speaker abstains from giving this kind of information; he is merely indicating the action that took place, without letting us know anything about duration or repetition, yes or no. This is why it is called the a -orist: it is “un-boundaried”, or undetermined:

The aorist draws no boundaries. It tells nothing about the nature of the action under consideration. It is “punctiliar” only in the sense that the action is viewed without reference to duration, interruption, completion, or anything else … The aorist can properly be used to cover any kind of action: single or multiple, momentary or extended, broken or unbroken, completed or open-ended. The aorist simply refrains from describing. (Stagg 1972:222)

Frank Stagg’s article on “The Abused Aorist” is a classic statement on this and well worth reading.

Pitfall 2: Word Studies

The second example of Greek magic has to do with word meaning. Sometimes every sense a word can have and numerous possible nuances or shades of meaning are brought to bear on that word in a particular passage. Never mind that the author did not have all those uses in mind when he wrote. In all probability, he only intended one – or perhaps two, if he used deliberate ambiguity – of those meanings. It may not be possible to be certain which meaning exactly was intended, but it certainly won’t be every meaning the term can possibly have all at once. To illustrate this tendency to overinterpretation, consider this commentary offered by a fictive scholar in the year 2790 (yes, 2790) based on an English text newly discovered around that time:

Consider also the subtleties implied by the statement that “her supervisor approached her.” The verb approach has a rich usage. It may indicate similar appearance or condition (this painting approaches the quality of a Picasso); it may have a sexual innuendo (the rapist approached his victim); it may reflect subservience (he approached his boss for a raise). The cognate noun can be used in contexts of engineering (e.g. access to a bridge), sports (of a golf stroke following the drive from the tee), and even war (a trench that protects troops besieging a fortress).

Society in the twentieth century is greatly illuminated by this text. The word patient (from patience, meaning “endurance”) indicates that sick people then underwent a great deal of suffering: they endured not only the affliction of their physical illness, but also the mediocre skills of their medical doctors, and even (to judge from other contemporary documents) the burden of increasing financial costs. (Moisès Silva, quoted in Ward 2009; this, too, is worth reading in full)

Let’s see if I can do better and steer free from these and other pitfalls in my reading project…

Preview

Here’s what I wrote early in November 2015, based on the first two chapters of Matthew.

An interesting word is used in Matthew 1:11 for “deportation” or “exile” (of Israel to Babylon). It is metoikesias, which includes the Greek word oikos, meaning “house”. We find it in English words like economy and ecology; the “eco” derives from the Greek word oikos. The preposition added to it, meta, suggests a change. So if taken at face value the word would mean a change of house or living place.

I am aware the reality was a lot more violent and horrible than this makes it sounds: house-change. But there may be a point in our lives where we need God to do something like this: uproot us and make us move to a different location: metoikesias. He did it with Israel around 586 BC. It happened to me five years ago, and it certainly was not fun. But I have to admit the change also greatly enriched our lives.

Okay, so lest I make myself guilty of the very kind of overinterpretation I criticized above: I admit this has little to do with the Greek text of Matthew; I am just fascinated by this word and by how the Greek language works. Let me indulge once more in this kind of reflection, and I will try to be more text-focused in future posts on my reading.

In Mt. 2:23 we find another word based on the Greek word oikos, this time a verb. This verb combines the noun oikos with the preposition kata, which adds a subtle nuance, even though the simple verb oikeo, without kata, has a similar meaning. The result (in both cases) is a verb that means more than simply to live somewhere or spend some time there. It means to settle in or indwell or inhabit a place.

There is a difference: do we merely “live” wherever we are, or do we indeed settle there and inhabit the place – and the circumstances? Jesus, it appears, did more than merely bide time in Nazareth.

References

Frank Stagg (1972), “The Abused Aorist”, Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 91(2):222-231

Mark Ward (2009), “Hat Steal”, http://byfaithweunderstand.com/2009/08/25/hat-steal/?utm_source=academic.logos.com&utm_medium=blog&utm_content=greekisnotmath&utm_campaign=logospro2015, accessed 14 December 2015