Last year in February, I wrote about my intention to read the New Testament in Greek and report regularly on Tumblr and other social media on my progress. So how did I do? Well, life happened. To be more precise, we unexpectedly decided to buy a house and move, which made much of the year look very differently from anything we had anticipated or planned for 2016. As a consequence, I have not published a post on Tumblr in months. This is part of the price we paid for moving…

You can also watch this content as a VIDEO PODCAST or listen to it as an AUDIO PODCAST

However, I have made progress in my reading, even if not as fast as I had hoped. By the end of the year, I made it to Colossians. When this issue comes online, I will be reading Revelation. So it is taking me several months more, but the end is in sight, and I should be able to finish soon.

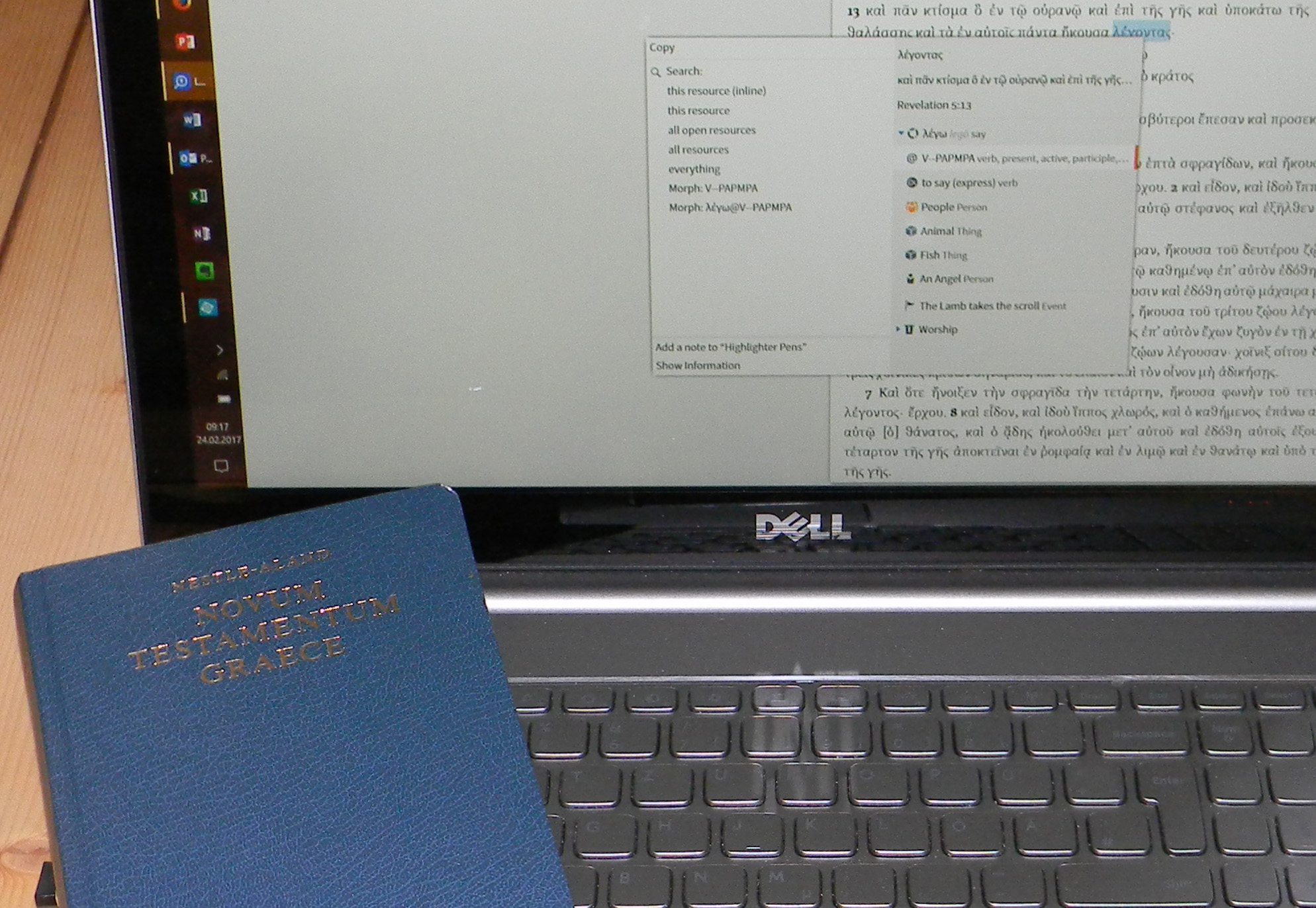

I wrote last year that I would do this with the help of Logos Bible software. This is a winner. I could not have done it within this timeframe without it. It is awesome to just click on a word and get its meaning plus a grammatical analysis in an instant. I admit, however, that one can get overly dependent on this feature. I would probably be more confident reading Greek without helps if I had not used Logos. But I am learning more in less time than if I had to page through a lexicon and a grammar all the time, and I am much further along.

As for my reading proficiency, I did a little test in Matthew, right at the beginning. At that time, I needed about 25 minutes to read a chapter. I repeated this test in January, with 2 Timothy and Philemon. I am down to 16 or 17 minutes for a chapter. My Greek has definitely improved this past year!

The Books

Here are some of my impressions.

Matthew and Mark were quite readable, John was easy, but Luke was a real challenge, both in vocabulary and in sentence structure. This also applies to the book of Acts. Clearly, Luke writes more sophisticated Greek. I knew this before, in theory, but now I have experienced it first-hand.

I was surprised that I found Romans and 1st Corinthians relatively easy to read (I had braced myself for my first encounter with Paul in Greek). My explanation is that the vocabulary of these two letters includes many theological terms that are discussed in literature, so many Greek words were familiar to me. Plus, I have spent a lot of time studying and teaching these two books, and the text is therefore familiar to me.

I was surprised again when 2nd Corinthians proved to be a real challenge. This is a highly personal letter of Paul, with not much theological vocabulary. Many of the words were therefore unfamiliar to me and I had to look them up.

Galatians through Thessalonians proved quite okay to read: familiar terms and familiar texts. The pastorals, on the other hand, were difficult. Again, they contain a lot of vocabulary that does not appear elsewhere in Paul and that does not necessarily consist of theological terms that are discussed in theological literature, so I was not familiar with them.

And then came Hebrews… This was a tough one to read, in my experience the hardest book in the New Testament (the ones following Hebrews are comparatively readable again, except for 2 Peter, also tough, but only three chapters long). It, too, has its own vocabulary. In addition, its author exploits the potential in Greek for dense and complex constructions. One has to pay close attention to know which phrase or clause goes what which subject or object.

This gave me a new and first-hand appreciation for the argument that Paul cannot have been the author of this book because of the Greek used. It is not simply the difference in terminology. It is not that hard to adjust your vocabulary to changing contexts. There was much else that was also new to me and took time to figure out. The author of Hebrews constructs his sentences in a different way.

Reading Greek

I have written this before, but one takeaway from this exercise is that our Bible translations are good. The translations that I am familiar with do not often appear to be poor or even wrong. I did occasionally wonder why translators changed the tense of a verb or chose a word different from the Greek word used, but these departures from the text did not lead to major differences in meaning. Reading the Greek text did add precision and depth, however, and above all force. This is highly subjective, of course, but I experienced it this way: these words, in Greek, are so powerful. And they come with a precision and nuance that is often hard to catch in a translation.

One way this precision and depth comes about is by combining words. The most common form is to add one or two prepositions (attachments) to modify the meaning of the original term, sometimes in subtle ways. This also happens in English, but not as often. Here are two examples.

1. Correction. 2 Timothy 3:16 uses the word epanórthōsis. It is translated as correction or improvement. It is a noun derived from the word orthós, which means straight or right, both in a literal and in a metaphorical sense (that is, true or correct). Two prepositions are added:

- Epí, often meaning on or above but also used for movement or aim.

- Aná, which can mean upward or anew, or subtly modifies the meaning in other ways that are not always easy to define.

Together, these three make for a stronger term, implying an upward or positive connotation for the envisioned straightening.

2. Avoid and devote. In Titus 3:2 and 3:9 Paul tells Titus and the church to “avoid” certain things (quarrelling and foolish controversies). In Titus 3:8 and 3:14 he tells them to “devote” themselves to good works. There is a contrast here that is obvious enough, especially in verse 8 and 9, but it is even more so in Greek. Paul uses two verbs derived from the verb hístēmi, to stand:

- Proístēmi. The prefix pro often means for or before. It refers to adopting a positive stance toward something, therefore “devote.”

- Periístēmi. The prefix perí often means around. This word refers to a negative stance: to ‘stand around’ means to do nothing or “avoid.”

In Greek, the contrast is explicit and obvious, more so than in English, where it only exists in the meaning.

Reading the text in Greek, then, does not usually lead to a different meaning but it frequently leads to a deeper or more nuanced understanding.

What’s Next?

Doing this has given me a fresh and intense encounter with the text. I love it. So what is next?

Obviously, the Old Testament. I fear, however, that my Hebrew needs some serious work before I can do this. But… there is the ancient translation of the Old Testament into Greek, the Septuagint. This was the Bible of the early church. It would to be an intriguing exercise to read those books in the version they used. I haven’t decided yet.

So What?

My aim in writing this is not to get you to read the Greek New Testament, unless this is something you’d really like to do and you feel ready for it. But perhaps there is something else you’d like to learn or read? A subject or question you’d like to consider and learn about? A book that you could read that would be a bit (but not too much) of a stretch?

How about choosing a learning project of your own, however small, to Create your own Learning Site? I think it would be worth it.