What, if anything, is our relationship with the Old Testament law? I was recently asked to teach an introduction to the Torah, the first five books of our Bible, in YWAM Heidebeek’s Bible for Life course. This gave me an opportunity to wrestle anew with this important question – important because it concerns a sizeable section of the Bible, because Christians give rather different answers to the question, and because, depending on the answer, the Christian life looks quite different.

You can also watch this content as a VIDEO PODCAST or listen to it as an AUDIO PODCAST

Preliminaries

So what about the law? I will attempt an answer in three parts spread out over two issues: a New Testament understanding (in this issue), reasons to study the law, and some practical considerations to help us in applying the law to our lives (in the next issue).

First, a clarification. The word “law” in the Bible is not always used in the same sense. In normal, everyday language “law” stands for a body of rules and regulations. In Scripture it is most often used to refer to the commandments and covenant mediated by Moses at Mount Sinai. It can also refer to the books of the law (Genesis through Deuteronomy). These two senses, Scripture and commandment (a body of rules and regulations linked with the Sinaitic covenant), are related but not identical. As we will see, it is a crucial distinction.

Second, an admission. This is a huge and complex subject. I cannot possibly cover all the relevant biblical material in these two issues. There cannot be an easy answer. In some ways, the law still applies (for one, it is quoted in the New Testament), in other ways, the law does not apply. To define these “ways” is the challenge.

Third, a suggestion. Before you continue with this issue, I propose reading through Exodus 21-23. This will give you a taste of the kind of material we are talking about. If you are not familiar with Old Testament law, reading these chapters may be a thought-provoking experience. You will probably find yourself intuitively agreeing with the condemnation of certain practices – but not all, and not with some of the harsh punishments prescribed either. You may well wonder about other elements, perhaps to the point of being shocked or considering them inhumane. The slave, free to leave after six years of service, has to leave without his wife and family (Ex. 21:4)? A man sells his daughter as a slave (Ex. 21:7)? Most likely, you will automatically assume some things do and others do not apply to us today. But why? Would you be able to give good reasons?

The subjects covered in these mere three chapters of Exodus are wildly diverse, and so are the forms. Some commandments are short and absolute statements. Others are relatively extensive case studies, beginning with a description of a concrete situation or event. Yet others prescribe rituals we don’t practice. It certainly reflects a very different type of society and culture than we live in. How can this material possibly be relevant to us today!? A full answer would take a book (at least), but let’s make a start by talking about the way the New Testament looks back on the Old Testament law.

Paul on the Law

Almost half the occurrences of the term law in the New Testament appear in Romans and Galatians alone. For this and other reasons, it makes sense to start with Paul.

Paul is empathetic about it. Believers are not under the law: “You are not under law but under grace” (Rom. 6:14). “But if you are led by the Spirit, you are not under the law” (Gal. 5:18). Because “you also have died to the law through the body of Christ” (Rom. 7:4). As a result, “we are released from the law, having died to that which held us captive, so that we serve in the new way of the Spirit and not in the old way of the written code” (Rom. 7:6). In Romans 7, Paul does not argue that the law has been abolished (although he will say something close to this in Ephesians 2:15). Instead, he points out that we have been crucified with Christ and, being dead, we are no longer under the law’s jurisdiction; it is as if we have moved to a new country. We are free!

In Galatians 3, Paul makes the point that from the start, the law was meant for a limited time only. It came after the promise, to function as a guardian, but only until the promised offspring would come.

This seems obvious enough; what more is there to say? Two things (at least).

First, one could get the impression that Paul sees a predominantly negative function of the law. The law serves to bring out sin (Gal. 3:19-22) or even increase it (Rom. 5:20). However, this is not the only function of the law. Paul does not hesitate to quote Scripture, including OT law, as authoritative in the life of believers. And he can describe the law in highly favourable terms: “The law is holy, and the commandment is holy and righteous and good” (Rom. 7:12; there is nothing wrong with the law, the problem is in us as fallen human beings).

Second, one should not conclude that anything goes: no law, no limits. Am I now free to commit murder and adultery, since I am not under the law? No. Paul does not teach what theologians call antinomianism (from Gr. anti and nomos, law). In Romans 6:14-19, immediately following his claim that Christians are not under the law, Paul anticipates and answers this very question. Christians are free from the law but not from righteousness. They have become “slaves of righteousness” (verse 18) and of obedience (not to the law, but to the “standard of teaching” received, verse 16). It is still wrong to commit murder, but not because the law says so.

In 1 Corinthians 9:19-21, Paul uses the phrase “the law of Christ” to depict this same paradox:

For though I am free from all, I have made myself a servant to all, that I might win more of them. To the Jews I became as a Jew, in order to win Jews. To those under the law I became as one under the law (though not being myself under the law) that I might win those under the law. To those outside the law I became as one outside the law (not being outside the law [literally: not being lawless] of God but under the law of Christ) that I might win those outside the law.

Paul is not “under the law,” although for the sake of fellowship with Jews he is willing to act “as one under the law,” so as to avoid giving offence. This explains for instance why Paul would circumcise Timothy (Acts 16:3) or take part in a Nazirite vow and present a sacrifice in the temple (Acts 21:23-26).

At the same time, he is not completely outside any law, because he is “under the law of Christ” (cf. Gal. 6:2). What exactly is meant with this phrase is debatable; is it the commandment to love, the teaching of Jesus, the example of Jesus, the abiding moral standards underlying much of the Mosaic law? But it is clearly not the law of Moses (otherwise Paul would contradict himself).

The Rest of the New Testament Other than the Gospels

Moving beyond Paul, there is simply too much material to cover (not least almost the entire letter to the Hebrews). I am going to limit myself to one passage. On one occasion, the question of Gentile believers and the Mosaic law became the subject of intense debate:

But some men came down from Judea and were teaching the brothers, “Unless you are circumcised according to the custom of Moses, you cannot be saved.” (Acts 15:1)

But some believers who belonged to the party of the Pharisees rose up and said, “It is necessary to circumcise them and to order them to keep the law of Moses.” (Acts 15:5)

From this debate we get confirmation for Paul’s position, which he argues at some length in Galatians, straight from Jerusalem and from the apostles and elders there. No, the Gentiles are not expected to keep the law of Moses:

Now, therefore, why are you putting God to the test by placing a yoke on the neck of the disciples that neither our fathers nor we have been able to bear? (Acts 15:10)

The decision was communicated by letter:

For it has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us to lay on you no greater burden than these requirements: that you abstain from what has been sacrificed to idols, and from blood, and from what has been strangled, and from sexual immorality. If you keep yourselves from these, you will do well. Farewell. (Acts 15:28-29; I assume this is not intended to convey that any other kind of vice, not included in this short list, is okay. Paul certainly does not conclude that freedom from the law means permission for licentiousness.)

Whatever the precise meaning of the exceptions (a good case can be made that they all relate to idolatry and sexual immorality, in Jewish eyes the prime pagan vices of the day, but this is a subject for another issue; see Witherington 2009:89-101), the conclusion is clear: Gentile believers are not expected to keep the law. We are free from this burden.

Jesus on the Law

But does this match the teachings of Jesus?

One difficulty in drawing conclusions from Jesus’ treatment of the law is, of course, that Jesus was very much under the law (Gal. 4:4!), as was his audience, in a sense that we are not. This is why I start with Paul, because he provides us with a mature reflection on the meaning of the law from a post-Easter and post-crucifixion perspective; Jesus spoke pre-Easter. This explains, for instance, why Jesus can say this:

The scribes and the Pharisees sit on Moses’ seat, so do and observe whatever they tell you, but not the works they do. For they preach, but do not practice. They tie up heavy burdens, hard to bear, and lay them on people’s shoulders, but they themselves are not willing to move them with their finger. (Mt 23:2-4)

A reason is given why his audience should heed the teaching: two parallel statements, essentially making the same point, the first in the form of a simple statement (“they preach, but do not practice”), the second adding graphic detail and emotional force. Do as they say, not as they do, so Jesus to his contemporaries. Should we, too, do what the Pharisees taught?

No. At this point, Jesus and his audience (all Jewish) are still within the horizon of the OT law and covenant, and we are not. Besides, the context is polemical. This is not a teaching on how to live with the law; the law is not the subject. Matthew 23 is an all-out attack on the religious leaders with plenty of hyperbole (deliberate exaggeration to make a point), irony, and sarcasm: by all means do what they say [well, for the most part, anyway; Jesus does not agree with everything the Pharisees teach], but don’t follow the example they set!

Jesus assumes the practice of the Mosaic law and cult in other places, too, in ways that don’t apply under the new covenant and in ways that became impossible when the temple was destroyed:

So if you are offering your gift at the altar and there remember that your brother has something against you, leave your gift there before the altar and go. First be reconciled to your brother, and then come and offer your gift. (Mt 5:23-24)

In this statement, Jesus assumes and accepts the sacrificial system of the temple, even though it would soon come to an end (which he knew; Mt. 24). He does similar things in other places, for instance when it comes to tithing (Lk. 11:42) or when quoting from the Ten Commandments to the rich young ruler (Lk. 18:21-25).

Yet sometimes, Jesus does something different. Striking is his teaching on food in Mark 7:14-23: food cannot defile a person. It is hard to read this in any other way than as Jesus, by implication, effectively abolishing or annulling (despite Mt. 5:17) a significant section of the law. In the same breath, he condemns several practices that the law also condemns:

And he said, “What comes out of a person is what defiles him. For from within, out of the heart of man, come evil thoughts, sexual immorality, theft, murder, adultery, coveting, wickedness, deceit, sensuality, envy, slander, pride, foolishness. All these evil things come from within, and they defile a person.” (Mk. 7:20-23)

What, then, is his enduring teaching on the law, for those who would come to believe in him after the resurrection?

The one passage where Jesus explicitly debates the question of the law at some length is Matthew 5. It turns out that his standard is far more stringent than that expressed in the Mosaic law. When it comes to things like murder or adultery, already our inner attitudes and thoughts count as transgressions, not merely the act itself. It appears Jesus goes for the real intent of a commandment. To replace an eye for an eye with turning the other cheek may look like abolishing one thing to replace it with something different, but this is not the case.

An eye for an eye placed a limit on revenge. This was an improvement (to killing the person who gouged out your eye or to knocking out all his teeth), but it did not go anywhere near far enough. Jesus builds on this limited first step in the law to bring it to its logical conclusion. If you practice an eye for an eye, you will have fulfilled the letter of the law, but you will have completely failed in fulfilling God’s true intent. In fact, you will not have fulfilled this commandment at all.

This implies that the law of Moses was never intended as a final, definitive, exhaustive, and complete statement of God’s standard. This statement is… Jesus!

The Law as a Type of Jesus

With this, we come to the heart of the law as understood in the New Testament. Jesus fulfils the law, not in the sense that he does the requirements of the law for us, but in the sense that he brings out the real and full intent and meaning of the law.

Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them. For truly, I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not an iota, not a dot, will pass from the Law until all is accomplished. Therefore whoever relaxes one of the least of these commandments and teaches others to do the same will be called least in the kingdom of heaven, but whoever does them and teaches them will be called great in the kingdom of heaven. For I tell you, unless your righteousness exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven. (Mt. 5:17-20)

In fact, Jesus is the law, the true embodiment and exposition of the law and of God’s standard for human life – he is, and shows us, what a human being ought to be.

A different way to put this is that the law is a type or a shadow that finds its fulfilment and antitype, its reality, in Jesus. This takes us back to Paul: Christ is the end of the law, its telos or aim (Rom. 10:4).

After all, the commandments of the law do not materialize out of nothing. Why are certain things right or wrong? They are so, depending on whether they are in line with God’s being and character. The true standard for what is right and true is in God. The Mosaic law begins to reveal what this is. Jesus completes it – a completion that can at first glance look like a contradiction, but never is.

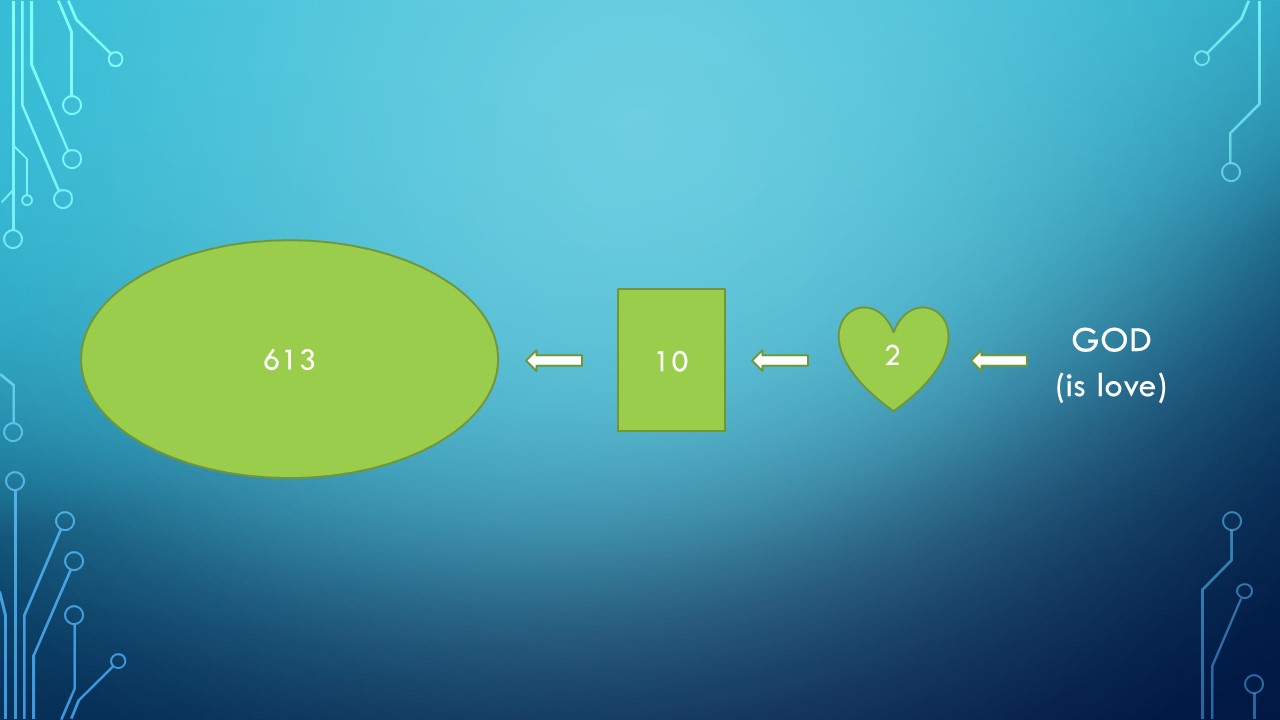

Here is another way to look at this (see the illustration below). By some counts, the law includes 613 commandments. As an aside, this is not many; it cannot possibly cover every situation, even in the simpler society of OT Israel. These 613 flow from the 10; they are the more detailed outworking and application of the Ten Commandments. Many commandments can be traced back to one of the 10.

These 10, in turn, flow from the two greatest commandments, that of love. When asked for the most important commandment, Jesus spoke of love for God and love for neighbor: “On these two commandments depend all the Law and the Prophets” (Mt. 22:40). And according to Paul, “the whole law is fulfilled in one word: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself’” (Gal. 5:14).

The Ten Commandments reflect this twofold love in their structure: the first four deal with our relationship to God, the others with our relationship to our neighbours.

All of the law, therefore, can be traced back to love. This is because love is the essential nature of God. And Jesus is the essential revelation of God, and therefore presents us with the ultimate standard of what is right and just and true. The OT law reflects this (him), but imperfectly. It provides a limited application of the fuller law for then and there, for a particular phase in salvation history, a particular and special nation, and a simple agricultural society. (By implication, and in anticipation of next month’s issue, it won’t be easy to apply this law to our very different stage in salvation history, not being a member of a nation-state that coincides with the community of God’s people or the ‘church,’ and living in a technological and highly complex society.)

Christians are not under this law (as commandment). But they are still called to a life of love and righteousness.

And this is where the law (as Scripture) can help. Because the new life of the Spirit within us needs instruction to know what righteousness and love look like. This instruction is found in the books of the Old and New Testament – including the law.

I like the phrase that John Walton and Andrew Hill (2004:117) use to express this: the law is “revelation rather than legislation.”

The law as Scripture still has something to offer. But how does this work?

To be continued!

References

Standard Bible Society (2001), The Holy Bible: English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Standard Bible Society)

John H. Walton & Andrew E. Hill (2004), Old Testament Today: A Journey from Original Meaning to Contemporary Significance (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan)

Ben Witherington III (2009), What’s in the Word: Rethinking the Socio-Rhetorical Character of the New Testament (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press)

Disclosure of Material Connection: Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission. If you purchase anything through such a link, you help me cover the cost of Create a Learning Site.