Matthew, Mark, and Luke have much in common, especially when compared with John. These three are therefore called the synoptic gospels (from Greek syn = together and opsis = view or seeing), since they provide a similar view of Jesus. The synoptic problem asks how this similarity can be explained. Biblical scholars have formulated numerous answers to this question, with one as the clear favourite: Mark wrote first, and both Matthew and Luke used Mark and an additional source called Q (from German Quelle = source). For this month, I take a fresh look at this and other explanations of the problem to see if I can come up with a clear conclusion or preference.

You can also watch this content as a VIDEO PODCAST or listen to it as an AUDIO PODCAST

Before going any further, I should state my point of departure (or bias, if you will) on this question:

- When it comes to authorship, dates, and priority in the New Testament, I have always considered the writings of the early church important evidence. This evidence points to Matthew rather than Mark as the first gospel to be written. I must add that I have changed my mind on this latter point. The church tradition on the order of the Gospels is not as unanimous as I thought. Plus, the case for what is called Markan priority (that is, Mark being the first gospel written) is strong.

- I have always been suspicious of a source (in this case, Q) that is entirely hypothetical. No fragment of a Q manuscript has survived, and we do not have any reference to this document.

My Approach

To solve the problem requires detailed comparison of the three synoptic gospels, verse by verse and paragraph by paragraph. This comparison considers both the order of individual narratives and sayings as well as the exact words used. The question is how similarities and differences can best be explained in terms of order of writing and use of sources.

Obviously, this is a task for specialists and it requires an enormous amount of time. I did not try to do this work myself but instead listened to a handful of established experts on this issue, representing four different answers. I won’t leave you to guess my sources the way Matthew, Mark, and Luke did. I found the following two books to be clear, understandable, helpful, and even enjoyable introductions:

- Mark Goodacre (2001), The Synoptic Problem: A Way through the Maze. This book is available as a free download in several formats and it makes for a great introduction to the subject. Goodacre has a clear preference (he believes Mark wrote first, but he does not believe in Q), but this takes nothing away from his presentation of the issues, and his dealing with the arguments is as fair and balanced as one can expect of someone with a clear opinion.

- Stanley E. Porter and Bryan R. Dyer (2016), The Synoptic Problem: Four Views. In this book, four defenders of alternative answers argue their case and interact with that of the others. I will very briefly summarize these four views below.

I studied the case these authors made for their respective view, in the expectation to come out with a clear preference. After all, if one or two of the evangelists copied one or two of the others, surely this is traceable; how difficult can this be?

Well, more difficult than I anticipated. Each view read in isolation was quite convincing – including the arguments against the other views. The problem is that different kinds of evidence pull in different directions. Perhaps this is an indication that the true explanation is more complex than we have been thinking. It certainly shows that the issue is far from decided: the synoptic problem is still a problem.

The Problem

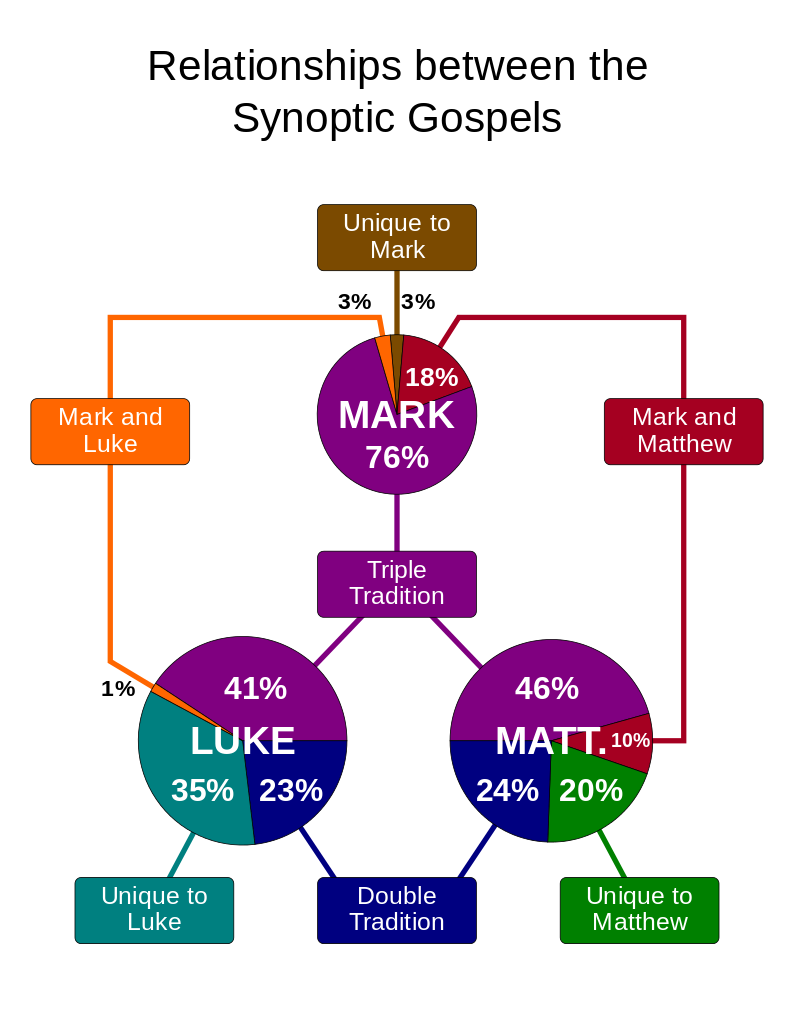

Before I give an overview of these four main views, let me restate the problem. The three synoptic gospels have much in common. Of 678 verses in Mark, over 600 appear in Matthew, Luke, or both (Porter & Dyer 2016:7). There is very little material that is unique to Mark (although Mark often gives more detail in his version of the same story). Roughly 230 verses are shared by Matthew and Luke but absent in Mark; most of this material consists of sayings of Jesus rather than narratives (Ibid.:8).

The similarity between the three synoptic gospels cannot be adequately explained by the fact that they are reporting the same story or sequence of events independently of each other. For this, the similarity both in the order of the individual stories and in the details of the wording is too great. Two eyewitness accounts of the same event will not have this much in common, especially not if they are this long. There are passages where the verbal agreement is so high that there has to be a literary relationship, that is, either direct copying by one from the other or copying by both from a shared source.

With this in mind, let’s turn to the four most common explanations. What I present below is by no means a complete summary of each case, but more a small sample of arguments. And if you want to see examples (it is fascinating to look at this in detail in various passages), you will have to download Mark Goodacre’s book; this issue will be long enough as it is.

The Two Source Hypothesis (with Q)

The most widely accepted explanation still is the Two Source Hypothesis: Matthew and Luke both used two sources, Mark and Q, but not each other. (Of course, both gospels also contain material that is unique to either Matthew or Luke, which may mean either of them used yet another source, but this is not considered in the naming of the hypothesis.) To put it differently, this hypothesis is based on two pillars:

- Mark wrote first, often referred to as Markan priority.

- Matthew and Luke wrote independently of each other. What they have in common, if it is not taken from Mark, must therefore derive from a second source: hypothetical Q.

A good case can be made for the first point:

- As noted, there is very little that is unique to Mark. It is easier to imagine Matthew and/or Luke adding to Mark than to imagine Mark abbreviating Matthew and Luke. Besides, if Mark wanted to produce a summary, why is his version of a story often longer than the one in Matthew and Luke?

- How can we best account for those few stories that are unique to Mark? Did Mark add them to his summary of Matthew and Luke? Or did Matthew and Luke decide to omit them? Most interpreters consider the second explanation more likely (it is not too hard to see why Matthew and Luke may have decided to drop precisely this material), and I have to agree.

- Mark’s Greek and style are simpler and rougher than that of the other two. It is easier to imagine they refined Mark than the other way around.

The second pillar is more debatable. It is argued that Luke did not know (and therefore did not use) Matthew:

- Much of the material Matthew and Luke share appears in Matthew in one of the five longer discourses. Luke has quite a bit of this material in different places, more spread out in his gospel. Would Luke have cut these discourses into pieces to include them somewhere else? Or was it Matthew who took this material from his source and completely reorganized it, with Luke staying closer to the original order of this source?

- Sometimes Matthew and sometimes Luke has what appears to be the original form of a saying and the more difficult text, the other one adjusting or interpreting it. If Luke were using Matthew, we would expect the original to always be in Matthew. An example: Luke 11:20 speaks of “the finger of God,” a phrase that is not easy to understand and therefore probably original; Matthew 12:28 uses an explanation: Jesus does this “by the Spirit of God.” Another example is the two versions of the Lord’s prayer (Mt. 6:9-13 and Lk. 11:2-4), where Luke’s simpler prayer clearly does not follow Matthew.

- When the three gospels differ from each other (verbally or in order), almost always Matthew agrees with Mark or Luke agrees with Mark; rarely do Matthew and Luke agree against Mark. “If Luke used Matthew, it is difficult to understand why his order never agrees with Matthew against Mark and why there are so few verbal agreements in Matthew-Luke against Mark” (Stein 1992:788).

The Farrer Hypothesis (No Q)

This alternative hypothesis is named after Austin Farrer, who published an essay “On Dispensing with Q” in 1955. This is the view of Mark Goodacre, who over the years has built a formidable case against Q.

Farrell and Goodacre agree with Markan priority but reject Q, considering it unnecessary. Instead, it is argued that Luke knew and used both Mark and Matthew. So how does Goodacre answer the three arguments in favour of Q just listed?

- Goodacre argues there are good reasons for Luke to rearrange Matthew’s material in every instance Luke has done this. There are also good reasons for material that Luke has left out. His gospel is organized very differently from Matthew (it is a travel account, without a topical structure), and Luke shows a tendency to abbreviate longer discourses in other places as well.

- Those who oppose Q call on oral tradition to explain cases where Luke seems to be more original: Luke knew an oral alternative (say, of the Lord’s Prayer) and ‘inserted’ this into his source Matthew. It is quite conceivable that Luke knew a different version of certain stories or sayings and replaced Matthew’s version.

- Matthew and Luke agree against Mark more often than the Two Source Hypothesis tends to acknowledge. There is a sizeable number of so-called “minor agreements.” Sometimes, these agreements are not so minor, as in the account of John the Baptist’s preaching (Mt. 3:7-12, Mk. 1:7-8, Lk. 3:7-17), where Matthew and Luke are in near-perfect agreement with each other but not with Mark. Defenders of the Two Source Hypothesis explain this as Mark-Q overlap, that is, Matthew and Luke both follow Q, not Mark, but it just so happens that Mark and Q partially overlap at this point (so neither Matthew nor Luke added something to Mark that the other copied; they both use Q). However, there is no evidence for this overlap, and it sounds like special pleading. Clearly, sometimes Matthew and Luke do agree with each other against Mark.

So perhaps it is not as unthinkable that Luke knew and used Matthew as the Two Source Hypothesis claims. At this point, an important difficulty becomes clear. We have to compare the three gospels verse by verse in order to try to explain the literary relationship and dependence between them. Unfortunately, at some points, this comparison leads in one direction, and at other points in a different one.

The Two Gospel (or Griesbach) Hypothesis

The Two Gospel Hypothesis argues that Matthew wrote first, then Luke, then Mark, using his two predecessors. I found this the least convincing explanation. Not even church tradition fully supports this view: although Matthew is generally considered the first gospel written, Mark is presented as writing in dependence on Peter’s preaching, not Matthew’s writing.

The Oral and Memory Hypothesis

Just when I thought I had at least reduced the spectrum of possibilities to two, Rainer Riesner, a German scholar, came and threw in the wildcard. He argues for the importance of oral tradition (narratives and sayings passed on by word of mouth), learning by heart, and the use of notebooks in education and as memory aids:

In the schools of philosophers it was very common for disciples to take notes on the teachings of their masters (Epictetus, Discourses 1.1-2; Porphyry, Life of Plotinus 4.12). The same procedure is known from early rabbinic circles … Books and notes served as aids to memorize sayings and stories in Hellenistic-Roman culture, and the same is true for Judaism (2 Macc. 2:25; Josephus, Ant. 4.209-11; 20.118). (Riesner 2016:105)

This implies there may have been much more material in circulation, both oral and written, than merely the few mentioned above (Mk., Q, special material used in Mt. and Lk.). Riesner therefore concludes:

From Jesus, the messianic teacher, to the Synoptic Gospels and beyond, there existed an oral tradition characterized by a flexible stability … From an early date there was an interplay between the oral and the written. Informal notes served as memory aids … The evangelists knew their materials from both oral traditions and written sources … The Synoptic Gospels are not mutually dependent but partially used the same intermediary sources. According to the foreword to his Gospel, Luke relied on the traditions of the eyewitnesses and many written accounts (Luke 1:1-4). This also indicates that the Synoptic phenomenon is best explained by a combination of the Tradition Hypothesis and the Multiple Source Hypothesis. (Ibid.:110-112)

Riesner may be right. But if he is, we will probably never resolve the synoptic problem because all the sources, especially the oral ones, are lost to us…

Still, the detailed comparison of verses and passages can yield a rich harvest as we wrestle with questions like: Why are these accounts different? And: What is the special emphasis of each gospel? Even if it does not lead us to a solution of the synoptic question, this kind of study is worth the effort.

References & Attribution

Illustration used: Popadius (2013), “The relationships between the three synoptic gospels,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Relationship_between_synoptic_gospels-en.svg (Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

Farrer, Austin M. (1955), “On Dispensing with Q,” in Nineham, D. E. (ed.), Studies in the Gospels: Essays in Memory of R. H. Lightfoot (Oxford: Blackwell), 55-88

Goodacre, Mark (2001), The Synoptic Problem: A Way through the Maze, https://archive.org/details/synopticproblemw00good

Riesner, Rainer (2016), “Orality and Memory Hypothesis Response,” in Porter, Stanley E. and Dyer, Bryan R. (eds), The Synoptic Problem: Four Views (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic)

Stein, R. H. (1992), “Synoptic Problem,” in Green, J. B. & McKnight, S. (eds), Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press), 784-792

Disclosure of Material Connection: Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission. If you purchase anything through such a link, you help me cover the cost of Create a Learning Site.