For last year December, I was asked to teach a week in Norway that included the book of Ezra. This offered me a rare opportunity. I don’t think I have ever taught this book before, so it gave me the chance to prepare a brand-new teaching on a book from scratch. Some months before, I did an issue on narrative criticism, and I decided to use this tool in preparing for class. I now present the results of a (very) simple narrative-critical analysis. My aim was to learn more about the author’s (or editor’s) point of view by paying attention to:

- Interpretation added by the narrator

- Actions and utterances by participants

- Repetitions

You can also watch this content as a VIDEO PODCAST or listen to it as an AUDIOPODCAST

Preliminaries

It is likely that Ezra and Nehemiah were originally one book. It is certainly treated this way in the Jewish Bible, and it wasn’t until the third century A.D. that the book was first split into two. Although I focused on the book of Ezra, I did therefore pay some attention to its continuation in Nehemiah.

Obviously, Ezra-Nehemiah has been composed using a number of sources: a memoir of Ezra, a memoir of Nehemiah (both memoirs written in the “I-“form, something not so common in the Hebrew Bible), various lists, and several official letters and edicts involving Persian kings. Some of the latter are in Aramaic, the official language of the empire and the language of international communication.

Finally, it should be noticed that the events of Ezra 1-6 considerably predate the rest of the book. These early chapters took place during the reigns of Cyrus and Darius, immediately after the exile, and cover the years between 539 and 516 B.C. Ezra did not move to Jerusalem until the seventh year of Artaxerxes (Ezra7:8), which is 458 B.C., approximately 80 years after the first group of Jews returned to Jerusalem. Nehemiah followed in the 20th year of Artaxerxes (Neh. 1:1, 2:1), which is 445 or 444 B.C. Interestingly, Ezra reappears in Nehemiah 8 and 12. Ezra and Nehemiah were contemporaries and their ministries partially overlapped, but they were not contemporaries of Joshua and Zerubbabel in Ezra 1-6.

The correspondence with Artaxerxes in Ezra 4:7-23 is out of place chronologically, and it relates to the rebuilding of the city, not of the temple. It may therefore be the background for Nehemiah. Presumably, it is placed in Ezra 4 because the subject is opposition, but it is not part of the time period covered in the rest of Ezra 1-6.

Reigns of Persian kings appearing in Ezra:

- Cyrus 559-530 B.C.

- Darius 522-486 B.C.

- Xerxes (Ahasuerus) 486-465 B.C.

- Artaxerxes 465-425 B.C.

Editorial Interpretation

The first thing that stood out to me is that the account in Ezra is remarkably matter-of-fact. It recounts what happened, and only rarely gives a comment or interpretation. This means we have to dig deeper to discover the author’s point of view, his standard of evaluation that leads us to the intended message.

The book does give us a few interpretations. That Cyrus permits the Jews to return and that there are those who respond is because “the LORD stirred up” their spirit (Ezra 1:1 and 5). The “people of the land” (Ezra 4:4) are at their very first appearance marked as “adversaries” (Ezra 4:1).

When the Jews restart their attempt to rebuild the temple in Ezra 5, they can do so because “the eye of their God was on” them (Ezra 5:5). They manage to complete it because the Lord “had turned the heart of the king of Assyria to them” (Ezra 6:22).

Several times the reader is told that the hand of the Lord was on Ezra and on those who were with him (Ezra 7:6, 9, 28; 8:18, 22, 31). We learn from the author that Ezra was skilled in the law of Moses (Ezra 7:6, 12) and what his intent was:

For Ezra had set his heart to study the Law of the LORD, and to do it and to teach his statutes and rules in Israel. (Ezra 7:10)

Whenever the law is mentioned, it is often made explicit that either Moses or God or both are its source. It is never the law of Israel; it is the law of God and of Moses (Ezra 3:2; 7:6, 10, 12, 14, 21, 25f; Neh. 8:1, 8, 18; 9:3, 14).

There is more but it is not much. It is sufficient, however, to establish that God is with them in this endeavour of return and rebuilding and that the law is of central importance to this book.

Indirect Evaluation: What People Say and Do

We learn a bit more through the words and actions of those who appear in the narrative. In Ezra 3, for instance, the people gather “as one man” in Jerusalem, rebuild the altar, and celebrate the Feast of Booths (Ezra 3:1-4). Shortly after, they begin with rebuilding the temple (Ezra 3:8). The laying of the foundation leads to celebration, praise, and great joy but also grief (Ezra 3:10-13). This section describing the initial return and the rebuilding of the temple finishes with a celebration of the Passover (Ezra 6:19-22).

Through all of this, we see more clearly what is central and important in the outlook of Ezra and its author. Obviously, this includes the temple and its cult. We also gain an impression of a community serious about following God’s Torah.

We get to know the “adversaries” (Ezra 5:1) through their actions as well, especially through the letter included in Ezra 4:7-16, a letter full of slander, flattery, and spin. When it is answered, they go “in haste” (Ezra 4:23) to Jerusalem and force a stop to the work going on.

It is worth noting that none of the edicts and letters by the Persian kings throw any negative light on them, not even the answer by Artaxerxes in Ezra 4:17-22 to the slanderous letter. True, Artaxerxes orders a halt to the rebuilding of Jerusalem (not of the temple), but he has good reasons and it is only “until a decree is made by me” (Ezra 4:21). Everywhere else, the kings give their full support. There is also a clear contrast to the slanderous letter in the second letter written by Persian officials in Ezra 5:6-17. As a result, the temple is finished “by decree of the God of Israel and by decree of Cyrus and Darius and Artaxerxes king of Persia” (Ezra 6:14).

This establishes that God is giving the people favour with the worldly powers and that these support the restoration that is taking place.

At least one more value point is communicated indirectly in the concluding chapters of Ezra:

After these things had been done, the officials approached me and said, “The people of Israel and the priests and the Levites have not separated themselves from the peoples of the lands with their abominations, from the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Perizzites, the Jebusites, the Ammonites, the Moabites, the Egyptians, and the Amorites. For they have taken some of their daughters to be wives for themselves and for their sons, so that the holy race has mixed itself with the peoples of the lands. And in this faithlessness the hand of the officials and chief men has been foremost.” As soon as I heard this, I tore my garment and my cloak and pulled hair from my head and beard and sat appalled. (Ezra 9:1-3; emphasis added)

Its importance is shown by the fact that the officials consider it necessary to inform Ezra, by Ezra’s strong emotional reaction, and by the amount of space given to the issue. I will have more to say about this in the next section.

Repetition

The richest insight into the purpose of this book comes through simply noticing repetitions. The one that is most frequent is that of the house of God. It appears right from the start in the edict by King Cyrus (Ezra 1:2-4), mentioned three times in three verses. Rebuilding this house is the explicit purpose of those who return (Ezra 1:5). Cyrus lets them to take the vessels of the house of the Lord with them (Ezra 1:7).

All in all, there are almost 50 references to the “house” of God in the book of Ezra, not counting occurrences of the word temple. It is less common in Nehemiah, especially in the first nine chapters. This is not surprising, considering Nehemiah is primarily about rebuilding the wall around Jerusalem. In the final four chapters, there are 14 references to the “house” of God. This alone establishes the temple as the number one thing on the mind of the author, but there is more.

Next in importance and in the sequence of the text is the law of God. It is first mentioned in chapter 3 in connection with the sacrifices and feasts. At that point, the altar is restored even though the rest of the house is still in ruins. The law becomes the main subject beginning in chapter 7, not surprisingly, with the return of Ezra the scribe. In these later chapters, too, the focus is on laws dealing with the cult in the house of the Lord, not with what we might call individual ethics. This includes a strong interest in priests, Levites, and other functions directly related to the house throughout Ezra and Nehemiah. We find the same focus in the covenant that the people make in Nehemiah 10; there, it is mostly about provisions for the service in the house of God.

There are two additional central themes in Ezra-Nehemiah. One is that of the wall that Nehemiah built. The other is that of separation and intermarriage. This subject takes centre stage both at the end of Ezra and at the end of Nehemiah. This suggests the author considers it of the utmost importance; it is perhaps his number one application for the original readers. The theme of separation first appears in the context of the Passover:

It was eaten by the people of Israel who had returned from exile, and also by every one who had joined them and separated himself from the uncleanness of the peoples of the land to worship the LORD, the God of Israel. (Ezra 6:21; notice the connection with ritual purity here, also in verse 20 – race or ethnicity is not the issue)

In chapter 9, it turns out that the people of Israel, including priests and Levites, “have not separated themselves from the peoples of the land” (Ezra 9:1), but have intermarried with them. The final two chapters of Ezra are entirely about this problem.

It is interesting to note the order of these major themes. First the house, then the law, and the wall only third. I doubt we would have chosen this order; it looks eminently impractical, and yet, it is precisely right.

As mentioned, the problem of separation and intermarriage comes up again toward the end of Nehemiah. In Nehemiah 9:2, “the Israelites separated themselves from all foreigners” (also in Neh. 13:3). It is “all who have separated themselves from the peoples of the land to the Law of God” (Neh. 10:28) who enter into acovenant with God. And yet, in Nehemiah 13:23-28, intermarriage with foreign women is still an ongoing problem.

Based on this, it appears the two books have a parallel structure:

Building the house – Building the wall

Opposition – Opposition

The law (Ezra comes) – The law (Ezra reads)

Separation/intermarriage – Separation/intermarriage

In addition, the Feast of Booths is celebrated twice, first in Ezra 3:4 and again in Nehemiah 8:14-18. Each book refers to the reorganisation of the Levites and the temple service by David (Ezra 3:10, 20 and Nehemiah 12:24, 36, 45f). The list of those who returned in the days of Cyrus is included twice as well (Ezra 2 and Nehemiah 7). Not everything in these books is repeated, and not all repetition is in the same order, but there is enough that it appears intentional.

A Normative Vision for the Returned Exiles

What emerges is a normative vision for those who have returned from exile. This connects the emphasis on the house of God and the law, especially its cultic commandments, with the importance of separation. Separation is all about cleanness and ritual purity. It is essential to the proper restoration of the service of the house of God and of worship in the midst of a community walking with God.

The lists fit in here as well. They document who belongs to the people of God and who are legitimate priests and Levites. The wall around Jerusalem is needed to protect and defend this renewed community of God’s people and to reinforce separation. For instance, it makes a stricter Sabbath observance possible (Neh. 13:14-22).

Wherever emotion comes out in these two books (Nehemiah has plenty of it), its aim is to strengthen devotion and zeal for God and his law.

Together, all of this serves to regain and guarantee continuity with the past (in life and worship) for the sake of the future. In other words, these themes (house, law, sacrificial cult, festivals, separation, Jerusalem) are to be the orientating centre of those who have returned. It provides them with a normative vision for life.

And for Us?

I leave you to contemplate the next step in this study for yourself, but here are a few questions to ponder . What implications does this have for life in the new covenant community? What does not carry over in a straightforward manner but needs redefinition? What does separation mean in our context? How does Ezra-Nehemiah speak encouragement to a NT believer?

Attribution

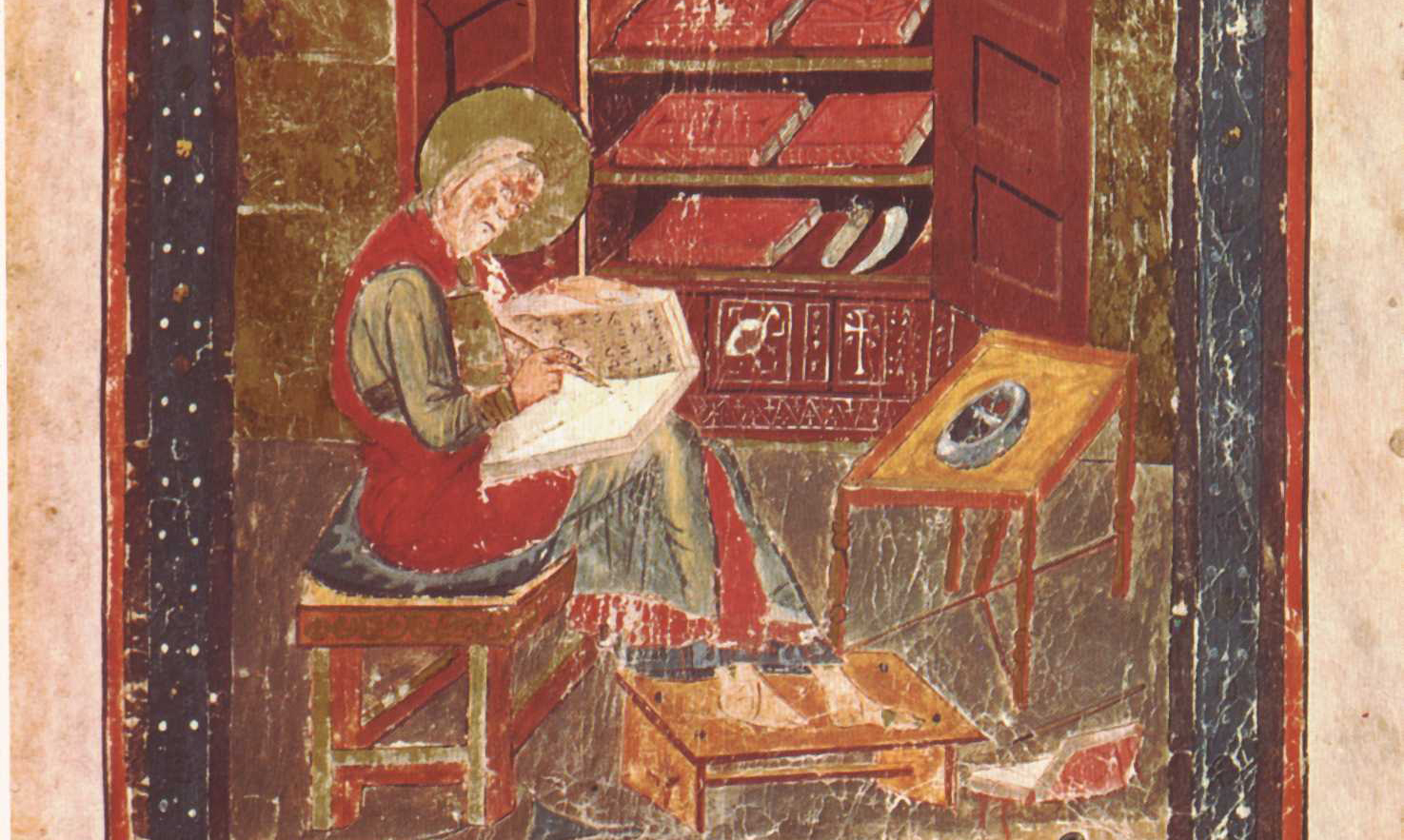

Ezra: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CodxAmiatinusFolio5rEzra.jpg, Public Domain

References

Standard Bible Society (2001), The Holy Bible: English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Standard Bible Society)

Disclosure of Material Connection: Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission. If you purchase anything through such a link, you help me cover the cost of Create a Learning Site.