Various gods and goddesses of Canaan make their appearance in the Hebrew Bible. It is easy to get confused. In Judges 2:13, for instance, the Israelites serve “the Baals and the Ashtaroth”; in Judges 3:7, they serve “the Baals and the Asheroth”. Ashtaroth and Asheroth – what is the difference?

This issue is meant as a stand-alone on the topic. At the same time, it forms the foundation for what I want to write on next: the presence of Canaanite mythology in the Hebrew Bible.

You can also watch this content as a VIDEO PODCAST or listen to it as an AUDIO PODCAST; to use as a handout, the text (including illustrations) can be downloaded as a WORD FILE or as a PDF

When it comes to the gods and goddesses of Canaan, we would not have much to go by if it were not for the fortunate discovery of a significant library of clay tablets at Ugarit. Ugarit is located to the north of Lebanon in today’s Syria. Strictly speaking, it is therefore not part of Canaan proper.

Nevertheless, the language, Ugaritic, is closely related to various Canaanite dialects, and the culture appears to have been similar as well. It is assumed that the mythology reflected in the Ugaritic texts that have been excavated closely resembles that of Canaan. Much is still unclear, and new discoveries or insights may make corrections of the reconstruction below necessary.

The Canaanite Pantheon

At the top stands El. The word el simply means god, but it is also used as a personal name. El is portrayed as wise and old. He is the progenitor of the gods and the creator of the world. One of his titles, significantly, is “Bull El” (Steiner 2016). Images of bulls and calves have been found in Canaan, associated with either El or Baal. They were probably understood as a pedestal for the invisible presence of the god, not a representation of the god himself.

His consort is Asherah, a mother goddess, who gave birth to 70 sons. These gods, one of which is Baal, form a divine council under the leadership of El or Baal and run the world.

Then there is Astarte or Ishtar, Ashtoreth in Hebrew. She also appears as the chief female deity. She was associated with fertility, sexuality, and war. She was widely worshipped in the Ancient Near East as the queen of heaven (cf. Jer. 44:17-19). In some texts, she is clearly distinct from Asherah, but there is also inconsistency in what is said of Asherah and Astarte, indicating conflation or confusion. The two may have merged in the first millennium BC (Steiner 2016).

Dagon or Dagan is mentioned as god of the Philistines in 1 Samuel 5:1-5 but is in origin a Canaanite deity. He is distinguished from El but both El and Dagon are at times referred to as the father of Baal and they may have merged into one.

Baal is the god of storm, the weather, lightning, and rain, which makes him very important. In a Mediterranean climate, the winter rains are vital to agriculture but not reliable. Baal is often portrayed as holding a club and lightning rods. It was Baal rather than El who led the gods and effectively ruled the world. Asherah may be so closely associated with Baal that she may at times have been considered his consort.

Hadad also appears as a storm god, in principle distinguished from Baal, but at times, as in the Baal Cycle discussed below, equated with him. It may be that Baal was originally a title, meaning Lord, and later developed into a personal name. Or perhaps Baal and Hadad were gods in different territories and were later discerned to be the same; after all, they represent the same forces of nature (Steiner 2016).

In the first millennium BC, Hadad was the national deity of Syria. His most prominent appearance in the OT is in the name of kings and others, for instance Ben-hadad, literally Son of Hadad, of Syria (e.g., 1 Ki. 20:1). His name also appears in Zechariah 12:11, where reference is made to “the mourning for Hadad-rimmon”, presumably a fertility ritual at the end of summer, when the rain-bringing storm god appeared to have died and needed to be brought back. See the Baal Cycle below for the background narrative.

Anat is Baal’s sister. She is called a virgin. She is a goddess of war and perhaps of love, although the latter is nowadays in doubt (Cornelius 2008). Anat has a volatile and violent temper; the Baal Cycle (discussed below) portrays her as

… engaged in a gruesome battle where she is “knee-deep” and “neck-deep” in the blood and gore of warriors – a circumstance that apparently brings her much joy … After the battle, she washes away the blood, puts on makeup, and sings a song about her love for Baal. (Balogh and Mangum 2016)

Except as part of geographical names, Anat is not mentioned in the OT, but she plays a crucial role in the Baal Cycle, as do the next two deities.

Mot is the god of the underworld and of death (although it may be more accurate to say he is death). His appetite – for human flesh – is unsatiable. Isaiah’s statement that God “will swallow up death forever” (Is. 25:8) is a pun on Mot’s nature.

Yam is the sea personified. The sea has fearsome destructive power; it was perceived and personified as an unpredictable, even evil force of chaos. Associated in some way is Lotan, the Canaanite name for Leviathan: a seven-headed serpent or sea monster killed in battle by either Anat or Baal.

I only mention several deities in passing. Molech or Milcom is the god of the Ammonites, usually linked with child sacrifice. Chemosh is the god of the Moabites. As everywhere in the Ancient Near East, sun and moon were both worshipped in Canaan as well.

The Baal Cycle

The Baal Cycle, a text written on a set of clay tablets found in Ugarit, consists of three parts. Part 1 describes the battle between Yam (the sea) and Baal. In part 2 Baal builds his palace on Mount Zaphon. Part three is about the conflict between Baal and Mot, the god of death. Many portions are damaged or missing altogether but below is a tentative reconstruction of the storyline.

Part 1: Battle with Yam. The first conflict is triggered when El decides – or perhaps is forced by Yam – to appoint Yam as king over the gods. For this, Yam will have to defeat Baal and seize his throne. Yam is a formidable opponent with powerful allies (sea monsters), but Baal defeats him with the help of a magic club he has been given. (As we have seen, Baal is often portrayed holding a club ready to strike.) Battles like this between cosmos (the ordered world) and personified chaos (non-order) represented by the sea are a common motif in creation myths of the Ancient Near East. In Canaanite mythology, however, there does not appear to be any link with creation. Baal’s victory guarantees the continued order and stability of the earth.

Part 2: Building the palace. The second part begins with a gruesome battle scene involving Anat, Baal’s sister, revelling in the blood and gore of the slaughter. Afterwards, Baal complains to her that he does not have a palace. This is not a small thing: Baal’s kingship is not secure and does not appear legitimate without one; what kind of a king does not have a palace? First Anat and then Asherah (here named Athirath) plead with El to permit this. The palace is built. “The story climaxes with Baal ‘enthroned in his house’ as ‘the one who reigns over the gods’” (Balogh and Mangum 2016). Baal prepares a feast and invites Mot, which may be an implicit call to submit to his rule and acknowledge his kingship.

Part 3: Conflict with Mot. It appears that Mot has taken offence. He threatens to eat Baal. In dread, Baal agrees to surrender to Mot. He enters the underworld, Mot’s domain. With Baal’s death, the land dries out and vegetation withers. After some time has passed, Anat attacks Mot, cuts him into pieces, winnows him, grinds him, burns him, and scatters the remains over the earth, also feeding them to the birds. Baal returns, and rain and fertility are restored. After seven years, Mot also comes back to life and revives the conflict. The two fight to exhaustion, but without resolution. Then, Mot hears that El has changed his mind, now supports Baal as king, and is threatening to take Mot’s throne away. Upon this, Mot acknowledges Baal as king and withdraws to his own realm, the underworld.

There is debate about what this myth represents. Many believe that it establishes or mirrors the seasonal pattern. In the dry summer half of the year Mot takes over and Baal is dead. He has to be revived or released from the underworld for rain and fertility to return at the end of summer.

Others argue that the myth seeks to explain catastrophic droughts: a period of several years in which little or no rain falls (cf. Gen. 40; 1 Ki. 17; 2 Ki. 8:1; ironically, here it is Yahweh who controls the rain and fertility, not Baal).

Canaanite Religion and the Bible

In the Hebrew Bible, Baal, Asherah, and Ashtoreth often appear in the plural: Baalim, Asheroth or Asherim (surprisingly, a masculine plural for the name of a female deity), and Ashtaroth. In addition, the name Baal can appear with a location added (Baal of Peor in Nu. 25; Hadad-rimmon in Zech. 12:11). This does not imply that there were multiple Baals and Asheroth; it refers to a local manifestation or cult of the respective god or goddess.

Asherah is also used for an object that could be cut down and burnt with fire (since that is what the law prescribes must be done with the Asheroth). It must therefore be of wood. The object probably represented Asherah in some way, not unlike an image, and had a function in the cult. We do not know any specifics. It is often presumed to be an Asherah pole, a holy tree, or perhaps even a grove. The latter is how the King James Bible translated the word, as did the Septuagint (the ancient Greek translation of the OT).

Obviously, then, from the time of Judges onwards, Canaanite gods and religion made inroads into Israel. The heyday of Baal worship in Israel came in the days of Elijah, when the Phoenician princess Jezebel launched a massive campaign to promote Baal.

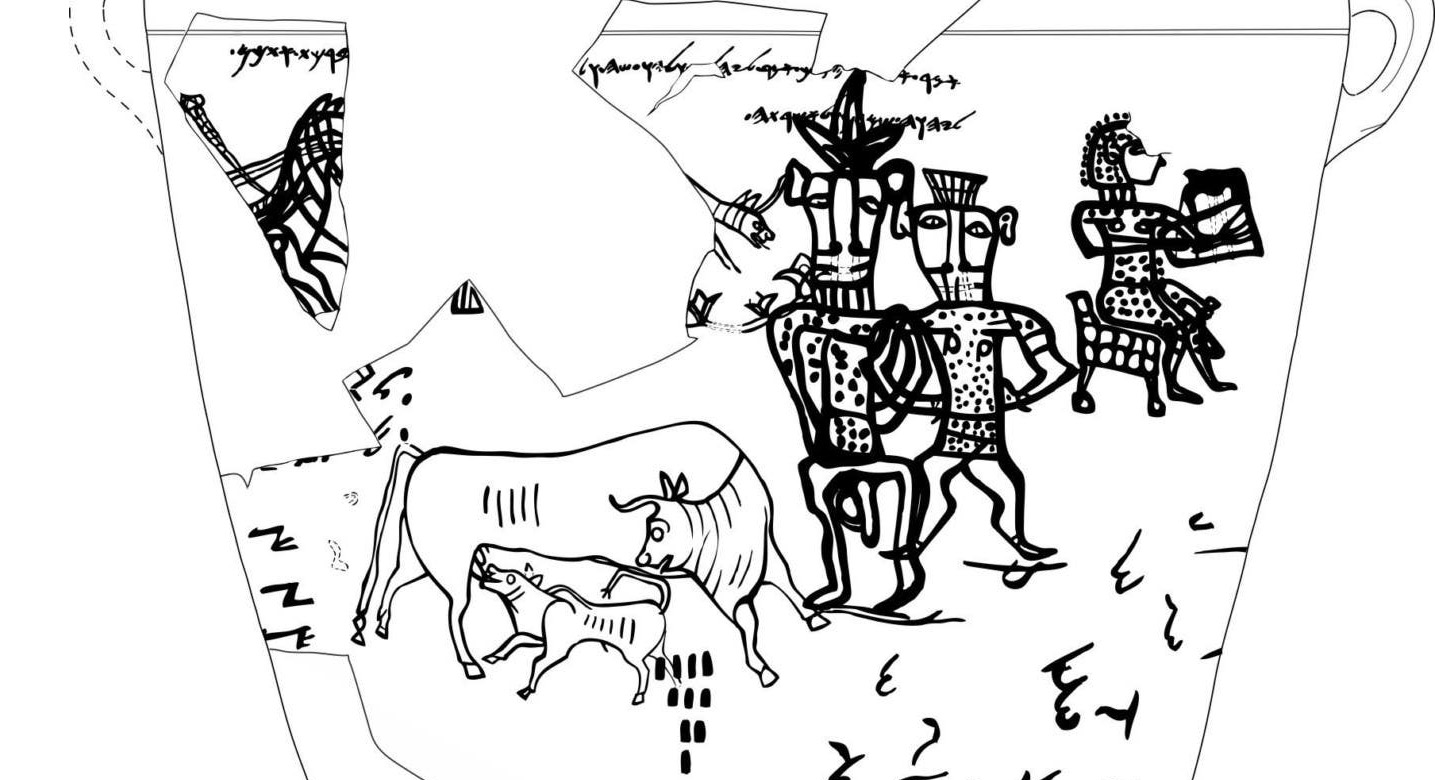

Possibly even more treacherous than this was a parallel development: mixing the worship of Yahweh and Baal. In popular and syncretistic religion in Israel, Yahweh could be equated with both El and Baal. As the illustration at the top shows, this could lead to associating Yahweh with Asherah as his wife – and representing him using the form of a bull or calf.

There may have been a tendency in Israel to equate Asherah with Asthoreth as well, perhaps even worshiping both together as the queen of heaven. Interestingly, hundreds of statuettes, known as pillar figurines (Downey 2020), have been excavated in Israel. They show a female holding her breasts. They are likely to represent either Asherah or Asthoreth, or both. Otherwise, their meaning is unclear: What is she offering? Is it nurture of some kind, symbolized by breastfeeding? Or is it fertility? Sex? Without any textual reference, it is hard to know.

Child Sacrifice and Ritual Prostitution

And so we come to recent debates regarding Canaanite religion. Traditionally, it has been held that the Canaanites were exceptionally depraved, especially in sexual practice, that they performed child sacrifice, and that the worship of Baal involved ritual prostitution. Nowadays, this is often challenged.

Depraved? Admittedly, we know relatively little about the actual practice of religion in Canaan, especially among the common people. We should not exaggerate Canaanite depravity. It needs to be kept in mind that the aim of Scripture in this context is to warn Israel for certain actions and their consequences. Its focus is therefore on the negative, describing it in strong language. In doing this, it is not wrong or untrue; it is deliberately one-sided.

Not everything Canaanite is always bad; Solomon needed Hiram’s help to build the temple (!), according to 1 Kings 5, and Elijah found refuge with a widow in the vicinity of Sidon (1 Ki. 17:9). Still, child sacrifice and cult prostitution are morally reprehensible; to the extent that these were practiced by the Canaanites, their culture would be open to censure.

Child Sacrifice? But did they? The phrase used in the OT literally means to make your children pass through the fire. Some interpret this as a dedication ritual: The child was not actually burned. This appears unlikely. The context of the phrase frequently implies more, and the horror and moral outrage of the law and the prophets when they confront Israel for this practice suggests something a lot less innocent.

But even if the Israelites engaged in child sacrifice, did the Canaanites? In those OT passages where a deity is mentioned, it is mostly Molech, the god of the Ammonites. There are exceptions, however: Deuteronomy 12:31 and 18:10 speak of child sacrifice as a Canaanite practice, and according to Jeremiah 19:5, children were sacrificed to Baal on the high places built for him (cf. Jer. 32:35).

It is true that we know little about early Canaanite practice. But later Greek and Roman sources are clear (and shocked). In antiquity, the Phoenicians – Canaanites from the Lebanese coast and their widespread colonies – were notorious for this practice. As Steiner (2016) summarizes:

Various Greek and Latin sources bear witness to Punic child sacrifice [Punic refers to the Phoenicians in the western Mediterranean]. They also attest to a great bronze statue of Kronos, in whose arms children were placed over a fire. Sacred precincts or cemeteries known as “tophets” have been discovered at several sites where the Phoenicians established colonies (e.g., Sardinia, Sicily, and Malta); at Carthage, thousands of burial urns filled with the charred bones of infants or small sacrificial animals and birds (which may have functioned as substitutes for children) have been found.

It may be possible to find alternative explanations for all of this, but I am not convinced. Where else did the Israelites and the Ammonites get the idea?

Cult prostitution? Because he was the storm god, bringing the rain, Baal played an important role for the fertility of the land. We have seen that Baal had to be released from the realm of the dead for rain and fertility to be restored to the earth. In this context, prostitution may have been understood as a magical act or a symbolic enactment, meant to induce the fruitfulness of the land: “His followers often believed that sexual acts performed in his temple would boost Baal’s sexual prowess, and thus contribute to his work in increasing fertility” (Corduan 2016).

However, such an explanation is widely questioned today: “There is little evidence for this”, concludes Steiner (2016). However, (1) little evidence is not zero evidence; (2) there is no evidence disproving the explanation; and (3) most of our sources are from the north of Canaan (Lebanon) and beyond (Ugarit), but Israel lived in the south, and there may have been regional or other differences.

There are two questions at stake. Was there sacred prostitution or sexual immorality as part of the cult, and if yes, what did it mean?

Despite the modern debate questioning it, the OT seems clear that sexual immorality was strongly associated with Baal worship. There even is a separate term, distinct from ‘ordinary’ prostitutes: the female form of a Hebrew word derived from the adjective holy, therefore presumably meaning cult prostitute. It will not work to argue that this term simply means consecrated woman and therefore priestess. Compare, for instance, how in Genesis 38:15 and 21 both terms are used to describe Tamar; no one mistook her for a priestess. See also Hosea 4:14, where prostitute and cult prostitute are used in synonymous parallelism (for examples of the association of sexual immorality with idolatrous worship see Nu. 25:1-3; Jer. 2:20 and 13:27; Hos. 4:13; Am. 2:7; see also the discussion in Brueggemann 2016).

As for its meaning, this is more difficult; since people back then knew what it meant, it did not have to be explained. Regardless of whether the explanation as magic fertility ritual is correct or not, Baal worship in Israel and the high places are associated with sexual immorality in the OT. Mixing sex and religion makes for a potent and seductive brew. Eugene Peterson (2005) captures the promiscuous and sexualized Canaanite religion as practiced by the Israelites very well in the Message when he translates the high places of worship as “sex-and-religion shrines”.

The Canaanization of God’s People

It should now be clear what happened to the Israelites once they settled amongst the Canaanites: They were canaanized. They reconceptualized Yahweh in the image of Baal. Worship forms were adjusted accordingly. The result was syncretism.

And this is where it gets practical. We, too, are in danger of getting infected with the values and beliefs of the culture that surrounds us. In the New American Commentary on Judges, for instance, Daniel Block (1999: 71f) points to a preoccupation with prosperity, “which turns Christianity into a fertility religion”. He also points to “our eagerness to fight the Lord’s battles with the world’s resources and strategies”. And when we embrace political or national agendas as part of our faith – canaanization also happens.

Our syncretism leads to cultural Christianity. The Christian Right. Or the Christian left. This happened in pre-war Germany, to the Catholic Church in Franco’s Spain, and to the Roman church under Constantine and in Byzantium. But it is always much easier to see it happen to others, in a different part of the world. So maybe, rather than point the finger at those other cases, each of us should ask:

How am I unduly buying into the idols and the ideological or political agenda of my age and my culture?

That is a much harder question to answer.

Attribution (in Order of Appearance)

Amplisound. 2020 <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ajrud.jpg> [accessed 11 February 2021] Public Domain

Jastrow. 2006a. “Baal with Thunderbolt” <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baal_thunderbolt_Louvre_AO15775.jpg> [accessed 11 February 2021] Public Domain

Jastrow. 2006b. “Baal with Right Hand Raised” <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Baal_Ugarit_Louvre_AO17330.jpg> [accessed 11 February 2021] Public Domain

Anon. 1017. “Nude Female Figure” <https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/323163> [accessed 8 February 2021] Public Domain

Rama. 2016. “Moulded figurine. Naked woman, hands maintaining breasts. Susa.” <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Naked_woman_holding_her_breasts-Sb_7742-IMG_0880-black.jpg> [accessed 8 February 2021] CC BY-SA 2.0 FR

References

All Bible quotations from: The Holy Bible: English Standard Version. 2001 (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles)

Balogh, Amy L., and Douglas Mangum. 2016. “Baal Cycle”, in The Lexham Bible Dictionary, ed. by John D. Barry, David Bomar, Derek R. Brown, and others (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press)

Block, Daniel Isaac. 1999. Judges, Ruth, The New American Commentary, 6 (Nashville, TN: Broadman & Holman Publishers)

Brueggemann, Dale A. 2016. “Baal, Critical Issues”, in The Lexham Bible Dictionary, ed. by John D. Barry, David Bomar, Derek R. Brown, and others (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press)

Corduan, Winfried. 2016. “Baal”, in The Lexham Bible Dictionary, ed. by John D. Barry, David Bomar, Derek R. Brown, and others (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press)

Cornelius, Izak. 2008. ‘Anat’ <https://www.bibelwissenschaft.de/stichwort/13361/> [accessed 9 February 2021]

Downey, April. 2020. “Judean Pillar Figurines”, Ancient History Encyclopedia <https://www.ancient.eu/Judean_Pillar_Figurines/> [accessed 8 February 2021]

Peterson, Eugene H. 2005. The Message: The Bible in Contemporary Language (Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress)

Steiner, Beth. 2016. “Canaanite Religion”, in The Lexham Bible Dictionary, ed. by John D. Barry, David Bomar, Derek R. Brown, and others (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press)

Tsumura, David Toshio. 2005. “Canaan, Canaanites”, in Dictionary of the Old Testament: Historical Books, ed. by Bill T. Arnold and H. G. M. Williamson (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press), pp. 122-32