Sin is universal. There is no one who does not sin. There is something fundamentally amiss with humans. How do we account for this? Asking this question brings us to a difficult and vexing topic: original sin.

We cannot credibly deny it; as the American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr famously quipped, “the doctrine of original sin is the only empirically verifiable doctrine of the Christian faith”. [Actually, he was quoting; so, who said it first? More on this quote in an appendix next time.] And after reading Richard Coleman (2021), I can see that it is a vital tool for the church to have a voice in today’s world; it is not merely a topic for theologians to argue about on gloomy Tuesdays or Thursdays, when there is nothing better to do. But first, what is it?

You can also watch this content as a VIDEO PODCAST or listen to it as an AUDIO PODCAST

Original Sin

The term does not appear in the Bible; it is a later, theological construct. It points to Adam and Eve’s act of transgression as described in Genesis 3. It reasonably assumes that this transgression is different from all other wrongful acts that followed it, with consequences far beyond the original perpetrators. The term original sin, therefore, can be used for this original transgression.

It is also used for the effect this first sin has on all humans, referring to something that, in a sense, resides with or within us. As such, it is a bit of a misnomer. It is not itself, at least not necessarily (depending on your understanding of it), sin; rather, it is what precedes actual sin.

And here, with original sin as an effect, the controversy – and the questions – begin. What exactly is that effect and the ‘something within us’ that results? Which components are involved? What is passed on and how?

Obviously, original sin includes corruption, but corruption of what? Is it bondage of the will? But if it is, and we are born with it, why would be held accountable for it? Is it the corruption of human nature? But what is human nature? The concept is abstract. McFarland (2010) prefers to locate original sin in the human self or person rather than in human nature. After all, it is the person who sins, not a nature.

Original sin is usually understood to mean that we are not able not to sin; whatever it is, that is its result. Are we, then, condemned for what we cannot avoid?

Is there in addition a component we may call original guilt? That is, are we guilty, quite apart from anything we did ourselves, but simply on account of Adam’s sin? This seems fundamentally unjust, and it may be very hard to justify such an idea. People have tried, as we will see, but something like ‘imputed guilt’ is not easily reconciled with basic conceptions of justice, even within the Bible: “the soul who sins shall die” (Ezek. 18:4, 20). Yes, there is also Exodus 20:5, “visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children to the third and the fourth generation of those who hate me”, but whatever else may be said about the verse, it puts a stop at the fourth generation – and therefore has nothing to do with any effects Adam’s sin may still have today.

Unfortunately, on original sin itself, there is not much in Scripture to go by. It is mostly Genesis 3 and Romans 5:12-21. There is Genesis 8:21, “the intention of man’s heart is evil from his youth” (a milder assessment than the one before the flood in Genesis 6:5; and notice it is from youth, not from birth). Plus, a long record of consistent human failure in the OT. Very early on, Joshua got it exactly right: “You are not able to serve the LORD, for he is a holy God” (Joshua 24:19). But why is this so?

After a brief look at Genesis 3, I will wrestle with Romans 5 in more detail; it truly is the most crucial passage. In all of this, I am forgoing questions of a historical Adam and the beginnings of the human race, a topic in its own right; I will simply work with the theology of both Genesis and Paul.

Genesis 3

Genesis 3 is the foundational story on our topic, but it does not explain much. It just tells the story. In fact, Genesis 3 states a whole lot less than most readers assume. Their (our) assumptions reflect later theological reflection, not the text. Genesis 3 does not even use the terms sin or fall.

The change that follows the event as described in Genesis 3 is limited, much of it relational. In more formal theological language, sin “caused a fundamental deformation in humanity’s relationship to God, each other, and the rest of creation” (McFarland 2010: 29).

This is a far cry from some modern renditions of the event that go so far as to even deny the validity of the laws of thermodynamics for creation before the fall – a view that is difficult to square with the world and its history as they present themselves to us.

Just to illustrate how much our assumptions shape our recollection of the text, at the risk of appearing overly precise, let me point out this: it isn’t Adam who transgresses. Literally, the text speaks of “the human” and the woman, and they both eat. From the start, there was a solidarity in sin, not a mere solitary act (or two); there is a collective component. Together. This will become important once we seek to explain original sin.

I close this section with one more example of how Genesis 3 states less than many believers think. Assuming we can speak of a ‘fall’, was it a fall from perfection, and if so, in what sense? Or should we limit it to a fall from innocence? How ‘perfect’ was Adam before the fall?

Again, we tend to exaggerate. Humanity in Genesis 2 was far from ‘finished’; it still had a long road of development ahead of it. We may well think too highly of Adam’s original perfection. Creation in Genesis 1 was good. Very good. But not perfect (yet).

Romans 5:12-21: The Problem

Now on to Romans 5. It is notoriously difficult. In defence of Paul, we should recognize he is pursuing a different question than we are. His interest is not original sin as such but understanding the work of Christ which saves from death. So, what is Paul saying?

12 Therefore, just as sin came into the world through one man, and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all sinned –

Unfortunately, Paul breaks off his sentence at this point without completing his thought (he may actually do so in verses 18 and 19). “One man” must be a reference to Adam. The sequence is:

- one man –> sin came in –> death came in –> death to all because all sinned

The explanation given for the concluding element in this chain (death) is, “because all sinned”. This is the real crux of the verse. In what sense did they all sin? Do people die because of their own sins? After all, that is the reason given in verse 12, they sinned. And that “death spread to all” possibly implies a process taking time, not an immediate and once-and-for-all event.

I have therefore often wondered if there is an alternative to the ‘classic’ reading, which claims all people die because of Adam’s sin, not their own. We might say: because all sinned in Adam, which is a widespread interpretation of Romans 5.

However, notice that this phrase is conspicuously absent in Romans 5; in fact, it appears only once in the Bible, in 1 Corinthians 15:22. If this is what Paul had in mind, it certainly is not what is in his text. And it was not an obvious concept or an established idea that he could expect his readers to know and therefore leave unmentioned and unexplained. If Paul meant to say, “in Adam’s sin we all sinned, and therefore we all die, because we sinned – in Adam”, he could have made that clearer.

(A note of historical interest: the assumed presence of “in Adam” in Romans 5 owes a lot to a mistranslation in the Latin Vulgate. The phrase “because all sinned” was misunderstood and translated as “in whom [that is, in Adam] all sinned”. Of course, that answers the question, but not for a good reason. It may be a valid explanation of what Paul has in mind, but the text does not say it, at least not with this phrase.)

To put the question differently, is the consequence that everyone dies an immediate one (that is, direct, because of Adam’s sin)? Or is it a mediate one, that is, indirect, with something in between:

- one man –> sin came in –> all sinners/sinful –> all sinned –> death to all

To jump ahead for a moment, verse 15 leaves us with the same question:

15 But the free gift is not like the trespass. For if many died through one man’s trespass, much more have the grace of God and the free gift by the grace of that one man Jesus Christ abounded for many.

“Many died through one man’s trespass”: directly or indirectly, with or without one or more steps in between?

Romans 5:12-21: Direct or Indirect?

Paul’s digression in verses 13 and 14 offers some support for the option that it is Adam’s sin that led to condemnation for all because it was the only transgression for which there was a law (“you shall not eat”, Gen. 2:17) – and “sin is not counted where there is no law”:

13 for sin indeed was in the world before the law was given, but sin is not counted where there is no law. 14 Yet death reigned from Adam to Moses, even over those whose sinning was not like the transgression of Adam, who was a type of the one who was to come.

For our interest, the next two verses offer much the same information as verse 15 in different terms:

16 And the free gift is not like the result of that one man’s sin. For the judgment following one trespass brought condemnation, but the free gift following many trespasses brought justification.

- one trespass –> judgment —> condemnation (presumably death; see verse 17)

17 For if, because of one man’s trespass, death reigned through that one man, much more will those who receive the abundance of grace and the free gift of righteousness reign in life through the one man Jesus Christ.

- trespass of one –> death reigns

I finish with Paul’s conclusion in verses 18 and 19, which appears to complete the thought left unfinished in verse 12:

18 Therefore, as one trespass led to condemnation for all men, so one act of righteousness leads to justification and life for all men.

- one trespass –> condemnation for all

19 For as by the one man’s disobedience the many were made sinners, so by the one man’s obedience the many will be made righteous.

- disobedience of one –> many made sinners

The two verses take us back to the dilemma we started with. Is condemnation ‘immediate’ or does verse 19 show us the ‘in between’?

Are we condemned to death based on Adam’s trespass? But how can that be just?

Or can we take the slightly softer route, by which all humans first became sinners, once Adam opened the door to sin, and are therefore guilty for their own sin, not Adam’s? To be sure, the latter option also leads to a difficult question of justice. If sin for fallen humans is inevitable, why are we held accountable for that which we cannot avoid? But at least we would have done something to earn the punishment.

Up to this point, I have ignored the parallel Paul draws between Adam and Christ. We should tread carefully here. Adam is merely a type (Rom. 15:14), not a full equivalent. He is only in some ways like Christ. Paul himself points out ways in which Adam’s trespass is both like and unlike Christ’s obedience. The crucial parallel, his main point throughout, is “through one man”.

On the whole, however, this parallel, together with Romans 5:13-14 (as pointed out above) plus the repeated idea of one trespass leading to condemnation, without clear hints of anything in between, make it more likely that the condemnation of death for humanity is immediate and follows from that one sin, not our own.

A Question of Justice

We thus run into a question of justice. How can a condemnation be just that is based on that first act of transgression (and therefore not based on things we have done ourselves)?

One classic Reformed answer is imputation: Adam’s sin is imputed to all his descendants, making them legally guilty; the condemnation is therefore legally correct. But how can it be just? As Oliver Crisp puts it:

Some Reformed theologians have argued that God immediately and directly imputes original sin from our first parents to all subsequent generations of humanity, and that on this basis we are reckoned to be guilty of original sin. But this seems a very strange arrangement, one in which the moral consequences of someone else’s sin are transferred directly to me by divine fiat, yielding guilt in me for something I did not do. For one thing, that seems monumentally unjust. (Crisp 2020: 38)

It won’t do to argue that rejecting condemnation because of Adam leads to rejecting forgiveness in Christ on the same grounds. It is one thing to be gracious; mercy is more than justice, not less. There is a framework for this even in human justice. But it is a different matter to punish a person for a crime he or she did not commit. This is less than just, and therefore unjust.

Perhaps our problem at this point is Western individualism and an overly legal mindset. When we allow for a more collective outlook, it becomes obvious that decisions of predecessors (especially ancestors) and of our collective whole, such as our nation, inescapably impact all members, including those not yet born. No man is an island.

There may simply have been no other way, no alternative; letting people live indefinitely would not have made things better! Once humans started down the road of independence into a sea of sinfulness, there was no way for them or their offspring, left to their own devices, to backtrack and be sinless again, free from the reign of sin and the sinful inclination.

God’s condemnation and verdict of death based on the first sin may therefore be proleptic, that is, in anticipation of the consequences that the beginning of sin had for the entire human race. From the start, God knew perfectly well where it would lead. And so, while there may not be original guilt, there does seem to be original condemnation.

In Closing: No Explanation

But this universality of death is one thing. Even more enigmatic is our universal tendency to sin. So far, we have found no explanation for the existence and transmission of original sin in the sense of an irresistible or inevitable tendency beyond the idea of ‘sin reigning’.

It is worth pointing to Romans 7. The human experience described there may well be Paul’s way of describing the inevitable inclination, something that remains mostly invisible in Romans 5.

“For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I keep on doing” (Rom. 7:19 ESV). The best of us, in our best and most noble efforts, when we try the hardest, too often fail to live up to our ideals and commitments. This – an empirical fact – points to a deep problem within us. It may well have led to God’s proleptic judgment in Genesis 3.

But what explains it?? (To be continued.)

Attribution

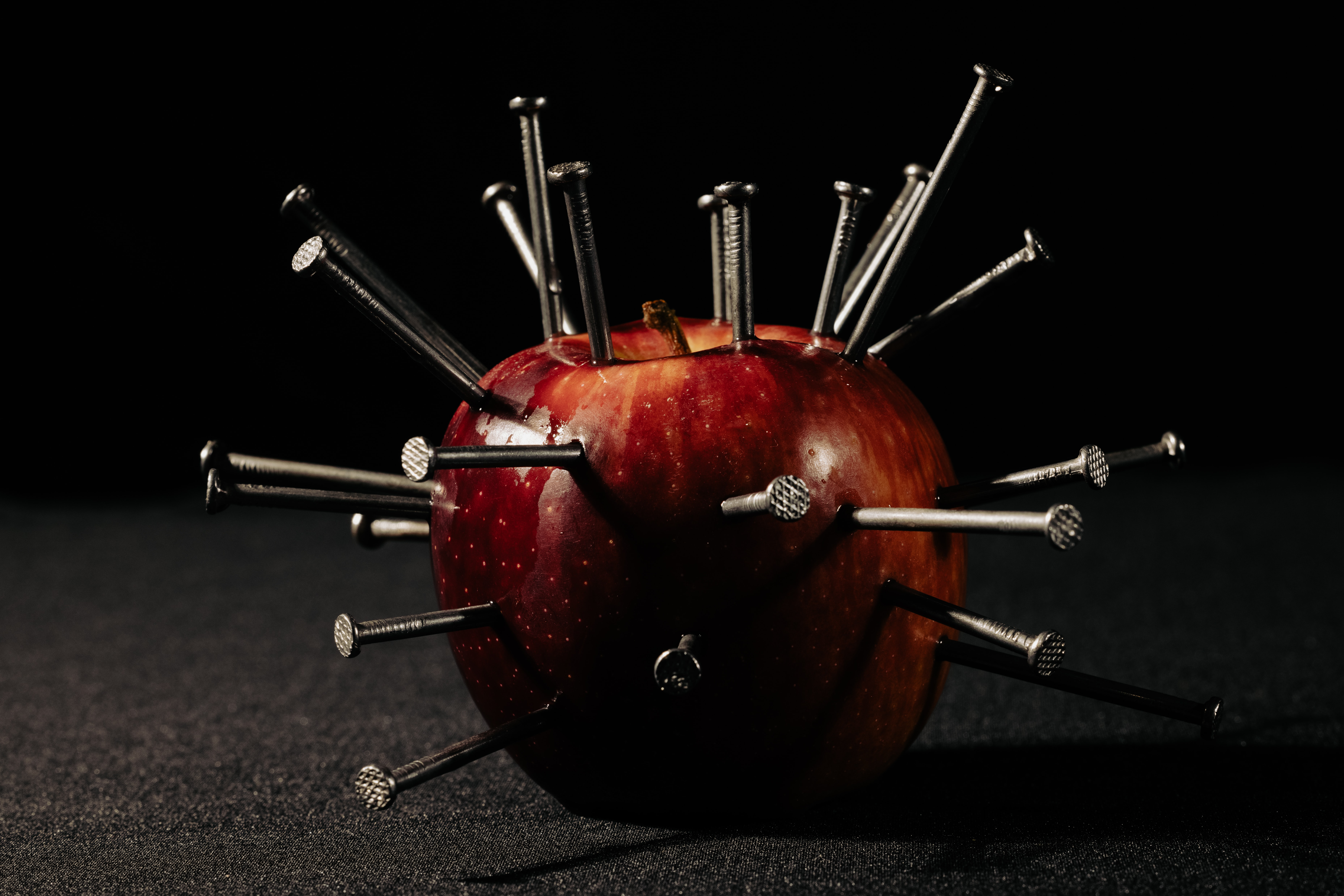

Engin akyurt. 2021. <https://unsplash.com/photos/LAdxcOfhbrc> CC0

CCXpistiavos. 2017. <https://pixabay.com/de/vectors/adam-bibel-bibel-bilder-2061819/> CC0

Darksouls1. 2016. <https://pixabay.com/de/illustrations/adam-und-eva-alt-baum-des-wissens-1649339/> CC0

CCXpistiavos. 2017. <https://pixabay.com/de/vectors/komische-charaktere-gott-adam-bibel-2061817/> CC0

References

Unless indicated differently, Scripture quotations are from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®, copyright © 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Chesterton, Gilbert Keith. 1908. Orthodoxy (Public Domain Books) Kindle Edition

Coleman, Richard J. 2021. Original Sin in the Twenty-First Century (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock)

Crisp, Oliver D. 2020. ‘A Moderate Reformed View’, in Original Sin and the Fall: Five Views, ed. by J. B. Stump and Chad Meister (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic)

McFarland, Ian A. 2010. In Adam’s Fall: A Meditation on the Christian Doctrine of Original Sin, Challenges in Contemporary Theology (Chichester, UK; Maldon, MA: Wiley-Blackwell)

Niebuhr, Reinhold. 2012. Man’s Nature and His Communities: Essays on the Dynamics and Enigmas of Man’s Personal and Social Existence (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock)

Orwell, George. 1976 (1945). Animal Farm (Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books)

Wiley, Tatha. 2002. Original Sin: Origins, Developments, Contemporary Meanings (New York: Paulist Press) Kindle Edition

Disclosure of Material Connection: Some of the links in this text are ‘affiliate links’. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission. If you purchase anything through such a link, you help me cover the cost of Create a Learning Site.