In a previous issue, I began an exploration of original sin. According to Genesis 3, ‘something happened’. Paul, in Romans 5, sees in this something the reason that all humans are under the condemnation of death. I remained unconvinced of the concept of original (or imputed) guilt but acknowledged original condemnation. And I finished part 1 without any explanation for the universal human tendency to sin, even though it is an empirical fact. Objective observation of human behaviour confirms it.

In this issue, I will look at proposed explanations for this inevitable bent toward sin.

You can also watch this content as a VIDEO PODCAST or listen to it as an AUDIO PODCAST

Explanations Past and Present

How do we account for original sin? Opinions differ and answers have changed over the centuries.

The biological model. The church father Augustine believed that original sin is passed on (transmitted) from generation to generation, together with or as part of human nature. In modern language, he considered it a near-biological process, akin to genetic inheritance. This makes it difficult to speak of our responsibility for it. Besides, sin or sinful inclination can hardly be biological. It is not in our DNA; there is no gene for sin. It turns out this is no explanation.

The absence of something. What if original sin is not the presence of something, but its absence, a lack? In medieval and Catholic theology, this lack is understood to be original justice, which Adam lost in the fall. Original justice was a divine gift that would have enabled humans to live in accordance with God’s will.

However, this looks a bit thin. Why would humans without this gift, in their natural, created (!) state, be fundamentally bent toward sin?

The relational factor. Alternatively, the absence could be that of a relationship with God. This was certainly lost after Eden. Humans born into a god-less vacuum would naturally bend inward instead of upward and end up living, in the most literal sense, a god-less life. It leaves us with little or no chance to live a righteous and godly life. We cannot love the God we do not know, much less love him with all our heart, mind, and soul as we should.

People have equated original sin with several ‘root sins’ that supposedly make up its essence: unbelief, pride, inauthenticity, a lack of love, and egotism. It appears to me, however, that original sin precedes all of these. They are its consequences, not original sin itself. Except, perhaps, for the absence or misdirection of love. This certainly comes close.

The realist understanding. We were all quite literally ‘in Adam’ because we are his descendants and therefore were ‘in his loins’, so to say. Admittedly, Hebrews 7:9f does play with this idea: “One might even say that Levi himself, who receives tithes, paid tithes through Abraham, for he was still in the loins of his ancestor when Melchizedek met him”. However, the opening phrase “one might even say” indicates the author knows he is pushing it here and merely uses it as a rhetorical ploy.

What if we apply this idea to everyone who became father or mother? Do all their descendants share in what their parents did before birth or conception?

I don’t see how it can be persuasively argued that we were ‘really’ present in Adam. And I am not sure it explains much even if we were.

The federalist model. Federal derives from the Latin foedus, which means covenant or alliance. In this model, Adam was, by divine covenant, our legal head or representative, much like a monarch or president represents a nation. Theologians therefore speak of federal headship. As the representative of humanity, Adam made the choice for us. We are condemned to death because of his transgression.

It is true that decisions made by, for instance, heads of state or other legal representatives have consequences for those they represent. However, we would not normally consider those being represented individually guilty. No German born after the Second World War is guilty of German crimes perpetrated during the war. Germans speak of historical responsibility, yes, but not guilt.

The imputation of Adam’s guilt to all his descendants answers the question (if it does that) at the expense of justice. Besides, nowhere in Scripture is Adam declared to be our head (the way Christ is), so how did he come to be our legal representative? Federal headship assumes what it has to prove.

In addition, it offers no explanation for the universal tendency to sin that plagues humanity. It is about guilt and condemnation; but how are we to explain universal sinfulness?

Sin as a force. Humanity’s declaration of independence in Genesis 3 placed us outside of God’s protection. We fell prey to the power of sin, an external force Paul refers to in Romans 6 and 7. In other words, we are up against evil and its agents.

I am not sure this offers a complete answer, but it is at least a partial one.

Psychological and existential models. Many modern readers take Genesis 2 and 3 as a timeless statement of human nature or existence. To them, the story is not about an event (or a process) in history. It expresses something that is generally true for humanity; the narrative is about all of us.

The problem with such approaches is that they make original sin a part of who we are, something that is essential to our humanity – a flaw in creation, it seems, which makes God responsible or at the very least exonerates us.

The sociological explanation. Every human is born into a human race already separated from God and in many ways under the sway of sin. If we understand human personhood as something that develops and unfolds gradually, it is easy to see that it must be shaped by its surroundings. From the beginning, there is no love of God. What else will this new person love and worship, idolatrously, but herself or others?

There is scriptural support for such a view:

And I said: “Woe is me! For I am lost; for I am a man of unclean lips, and I dwell in the midst of a people of unclean lips; for my eyes have seen the King, the LORD of hosts!” (Is. 6:5 ESV)

The fool says in his heart, “There is no God.”

They are corrupt, they do abominable deeds;

there is none who does good.

The LORD looks down from heaven on the children of man,

to see if there are any who understand,

who seek after God.

They have all turned aside; together they have become corrupt;

there is none who does good,

not even one. (Ps. 14:1-3 ESV, emphasis added; cf. Ps. 53:1-3)

Psalm 51:5, “in sin did my mother conceive me”, may fit in here as well. It is often taken as a reference to original sin, and probably rightly so. But the sin is not David’s. And it may not be his mother’s either, at least not hers only or specifically. It is an existing reality into which David was born, and it may well be that of the entire human race.

Presumably, there is a solidarity in sin that turns us, collectively, away from God.

And the Winner Is?

You may have noticed that in the above, I do not argue for one definite answer – on purpose. The explanations for original sin have changed over the centuries; the empirical fact remains.

I will try to summarize. The universality of original sin, it seems to me, includes a social component: we are born into autonomous and rebellious humanity.

It also includes a relational component: we are born already separated from God, in relationship with sinful human beings but not with him. As a result, we do not love or worship God. In fact, we don’t know him. Instead, we adopt as our own the human autonomy chosen by the human and his wife when they ate the forbidden fruit.

As a result, we each become our own, woefully inadequate centre as we bend inward. We willingly follow our disordered desires into actual sin.

There is a spiritual component as well: the world is under the power of Sin (capital S) as a force.

Does this adequately explain original sin? I am not at all sure that it does. It may be that sin, at the deepest level, defies explanation. Like evil, it literally makes no sense.

Its Importance for Today

At the start of this exploration, I mentioned Richard Coleman (2021). I do not share the way he reads Genesis or his understanding of original sin. But I did like some of the implications he points out for today. He speaks of theology “armed with the enduring truth of original sin” (ibid.: 8), quite a radical idea. How will that help us? Two points.

1. Original goodness. First, Coleman balances original sin with a concept of original goodness. We usually think of it under the term image of God. But however we put it, we must not lose sight of this other side of human existence. It is easy to make too much of it, but it would equally be an error to leave it out altogether. We are in every aspect of our being corrupted but not entirely and purely evil. Unlike Satan, whose fall was total and complete, ours is not. Rather, we are this weird and inconsistent mixture of the best – or at least good – and the worst. There is our worst self and our best self, and much in between.

Humanity is noble, with the original dignity not entirely lost, although it is broken. That brokenness from birth is original sin.

2. Healthy caution. One hugely significant practical consequence is, and this is the second point: “We are not as good as our ideals” (ibid.: 5).

This is one reason why communism failed so spectacularly. Too often, its leaders exempted themselves from hardship and lived a life of privilege. As George Orwell (1976: 114) satirized: All animals are equal but some animals are more equal than others.

We fall short of our best intentions and ideals. Knowing this (and humanity seems prone to forget) should lead to caution. Such caution is especially important when a brave new world with exciting breakthroughs is upon us – such as the promise of AI, genetic engineering, and the possibility of age reversal leading to much longer lifespans.

Not to spoil the party, but let’s be careful, and keep our eyes open. And with “us” I don’t mean Christians only; everyone, regardless of what name they prefer if original sin is not to their liking, should be aware of this perennial pitfall. We are not as good as our best ideas.

Perhaps G. K. Chesterton put it best:

But Christianity preaches an obviously unattractive idea, such as original sin; but when we wait for its results, they are pathos and brotherhood, and a thunder of laughter and pity; for only with original sin we can at once pity the beggar and distrust the king. (Chesterton 1908: 150)

Original goodness and healthy skepsis. Therefore: pity the beggar. Distrust the king.

Appendix: Empirically Validated

So, who said it first? Tatha Wiley gets it almost right:

Reinhold Niebuhr once cited a remark quoted in the London Times that “the doctrine of original sin is the only empirically verifiable doctrine of the Christian faith.” (Wiley 2002: kindle loc. 2534f)

She adds, in a footnote (ibid.: kindle loc. 3332): “His remark reflects a sentiment expressed by G. K. Chesterton”. Her source is Niebuhr himself (2012: 24; originally published in 1965):

I still think the “London Times Literary Supplement” was substantially correct when it wrote some years ago: “The doctrine of original sin is the only empirically verifiable doctrine of the Christian faith.”

Unfortunately, I could not retrieve Niebuhr’s source or its author. Wiley is correct that G. K. Chesterton said something like this several decades earlier:

Certain new theologians dispute original sin, which is the only part of Christian theology which can really be proved. (Chesterton 1908: 7)

The following quote is also widely ascribed to Chesterton on the internet, but I have not been able to find a reference for it; I am not sure if he did indeed coin it or if he did so using these exact words:

Original sin is the only doctrine that’s been empirically validated by 2,000 years of human history.

Attribution

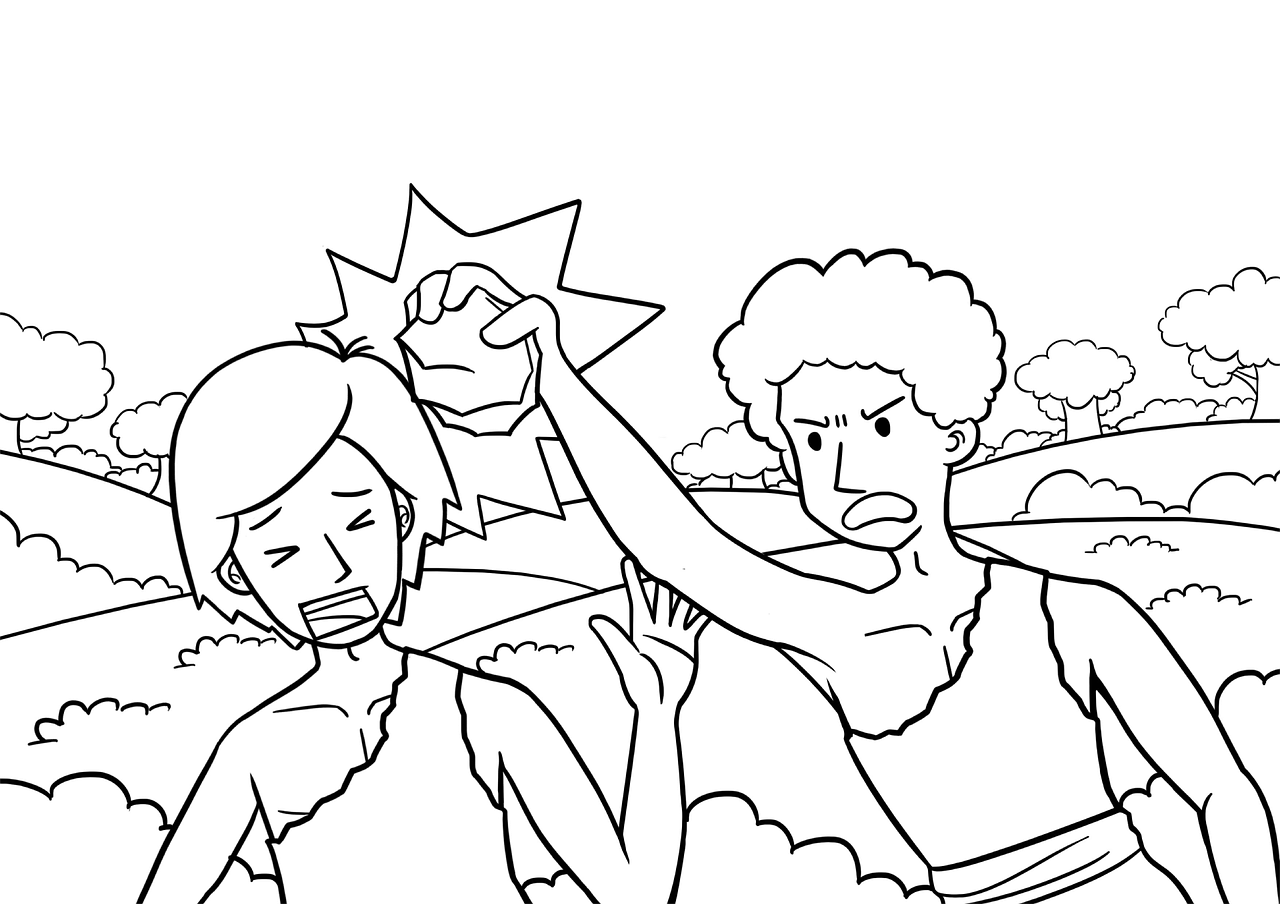

CCXpistiavos. 2017 <https://pixabay.com/de/vectors/abel-bibel-bibel-bilder-kain-2061823/> CC0

Smpratt90. 2017 <https://pixabay.com/de/photos/familie-neugeborenes-baby-kind-2610205/> CC0

Geralt. 2022 <https://pixabay.com/de/illustrations/ukraine-russland-köpfe-familie-7055808/> CC0

Ibid. 2022 <https://pixabay.com/de/illustrations/stress-burnout-verzweiflung-7453430/> CC0

Pixel2013. 2017 <https://pixabay.com/de/photos/gänse-gans-familie-gänsekücken-2494952/> CC0

GDJ. 2018 <https://pixabay.com/de/vectors/social-media-verbindungen-vernetzung-3846597/> CC0

planet_fox. 2020 <https://pixabay.com/de/photos/obdachlos-penner-armut-person-5283148/> CC0

References

Unless indicated differently, Scripture quotations are from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®, copyright © 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Chesterton, Gilbert Keith. 1908. Orthodoxy (Public Domain Books) Kindle Edition

Coleman, Richard J. 2021. Original Sin in the Twenty-First Century (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock)

Crisp, Oliver D. 2020. ‘A Moderate Reformed View’, in Original Sin and the Fall: Five Views, ed. by J. B. Stump and Chad Meister (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic)

McFarland, Ian A. 2010. In Adam’s Fall: A Meditation on the Christian Doctrine of Original Sin, Challenges in Contemporary Theology (Chichester, UK; Maldon, MA: Wiley-Blackwell)

Niebuhr, Reinhold. 2012. Man’s Nature and His Communities: Essays on the Dynamics and Enigmas of Man’s Personal and Social Existence (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock)

Orwell, George. 1976 (1945). Animal Farm (Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books)

Wiley, Tatha. 2002. Original Sin: Origins, Developments, Contemporary Meanings (New York: Paulist Press) Kindle Edition

Disclosure of Material Connection: Some of the links in this text are ‘affiliate links’. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission. If you purchase anything through such a link, you help me cover the cost of Create a Learning Site.