Good questions are extremely valuable. What makes a good question? One key indicator is that the answer is not immediately obvious. The answer may even continue to evade us. This must not lead to frustration. It can also open up room for repeated reflection and accumulating understanding. The present title – how do we live well? – is such a question.

The question first occurred to me while preparing to teach an introduction to the Torah, the first five books of the Bible. I don’t remember what came to me first: the question or the realization that this, Torah, the five books I was looking at, is the place to start. The question stuck and haunted me as I continued to prepare.

NOTE: After ten years of writing an issue each month and eight months on a sabbatical from writing, I am back. There is so much to learn! I hope you enjoy sharing my journey of discovery.

You can also watch this content as a VIDEO PODCAST

An Instruction Manual?

What does it mean to live life well? It must be one of the most important questions we can ask. Notice that I am using the plural (“we”). “How do I live well?” is a very different question. I don’t believe life can be lived well in isolation; it has to be “we”.

So, how do we live well? Many of us think of the Bible as an instruction manual intended to answer precisely this question. Indeed, in some ways it is. It is not a bad metaphor.

However, for the most part, the Bible’s literary form is anything but that of an instruction manual. It does not provide that kind of clarity. There are exceptions. One book that in many parts does read like a manual is Leviticus. But ironically, most of these instructions are not practiced by us today.

We have reasons for this, good reasons, but it illustrates the point: in the main, the Bible is not straightforward the way we expect of an instruction manual. If it were, there would be fewer theological controversies and far fewer denominations. Why did God not make it clearer?

A Book of Universal Principles?

A few months ago, I read a science fiction book by Ian M. Bank, Against a Dark Background. Let’s say I have read better books than this. But one element stuck with me. Part of the storyline is a quest to find a lost book. Its title is The Universal Principles.

When it is found, it is encased in titanium. On opening the encasement, it turns out the entire book has turned to dust. Nothing remains but the engraving on the encasement: its title, a dedication, and one principle: THINGS WILL CHANGE.

Things will change. This feels too relativistic for my taste. Is change really the only universal principle? Still, it illustrates an important point: what ‘universal’ principles can endure through time and apply across all sorts of situations? And if such ‘timeless’ truths could be articulated, would they be of much practical use?

Perhaps we should not be looking for timeless principles (what is that, anyway?). More helpful is learning how principles play out in real-life situations, rooted in particular contexts – practical, embodied applications of values that can guide our actions. This is what we find in the Torah: stories and principles grounded in the lived experience of Israel. Instead of abstract, universal truths, we find a narrative full of concrete examples that offer guidance for life.

ABC

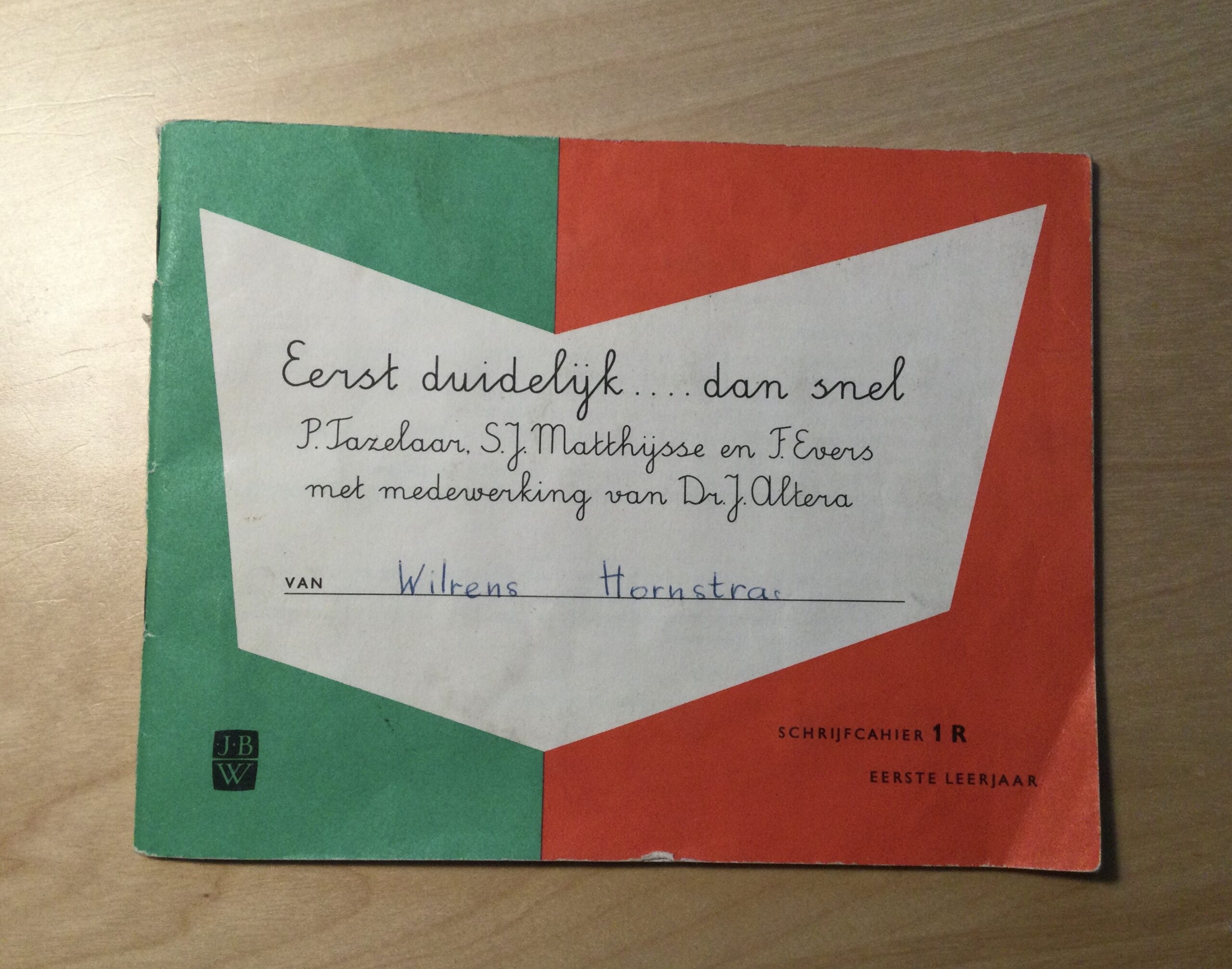

What we find in the Torah, then, is not an overview of universal principles but something more akin to learning the ABC. It is like learning how to write in first grade. The illustration shows one of my earliest writing booklets, now more than 55 years old. You can probably tell learning this was not easy.

How do we learn to write? Letter by letter, and with lots of practice.

How do we learn to live well? How did Israel learn to live well? In much the same way: precept by precept, with plenty of practice. And hard thinking.

For Israel, this process was initiated at Mount Sinai. They were being trained to live righteously, to be a nation, to establish a society. But Sinai was just the beginning. The particulars of doing the right thing are not always obvious. It is not possible for a single book or even an entire library to cover all possibilities and thus always point to the right course of action. The Torah does not even try. It gives legislation for a goring ox (Ex. 21:28-32) but not for an aggressive dog; do your own thinking!

More than anything, the Torah inculcates foundational values, the ‘letters’ of the alphabet: no idols, justice, compassion, love, truth and truthfulness, life. Above all, love, because it is the fulfilment of the law (Rom. 13:8-10) and its greatest commandment (Mk. 12:30f). And life because it is the very purpose of the law: choose life, that you may live (Deut. 30:19; John has a similar purpose and emphasis, e.g., “that you may have life”; John 20:31). The Torah functions as a training guide for living.

Not for Professionals

But isn’t the Torah a book of law? In our modern legal systems, law books are written for professionals, that is, lawyers and judges. Most of us have never looked into the actual law codes of our various nations. If we did, we may well have found the dense legalese unreadable.

But the Torah is different. For example:

- Torah means instruction, which is broader than just law.

- Much of it consists of stories (that instruct).

- It was meant to be heard – and later, read – by all Israel, not just by professionals.

Its intended audience was not legal experts and professionals but ordinary Israelites. Its aim was not to train lawyers and judges but to teach every Israelite how to live well in community with others. In other words, the law in the Torah is not a legal text but an educational text.

The same appears to be true for other so-called law codes from the Ancient Near East as well. The most famous one, that of Hammurabi (ca. 1750 BC), inscribed in stone, was publicly posted for all to see. It is widely believed to be a theoretical work, of scholarship or wisdom, rather than to have functioned as an actual law code used in a system of justice. Its function, too, was educational rather than legal.

The Torah presents us with an alphabet – an ABC – that helps us begin thinking about foundational questions, like the one I started with. Its purpose is not to create lawyers but to cultivate justice, compassion, and integrity in the hearts of ordinary people, that they (we) may live.

References

King, Leonard William. 1915. The Code of Hammurabi <http://www.general-intelligence.com/library/hr.pdf> [accessed 25 March 2021]