As a phrase, “the image of God” appears only once in the Bible, in Genesis 1:27. In the OT, the idea is also referred to in Genesis 5:1 and 9:6. That is not much. As a result, there is an interpretational challenge. Throughout the centuries, interpreters have debated without agreement what, exactly, this image consists of. Is it our rational capacity? Is it language or abstract thought? Is it our ability to relate or to love? Is it our ability to enter into a relationship with God? Or is it one of several other options that have been proposed?

You can also watch this content as a VIDEO PODCAST or listen to it as an AUDIO PODCAST

This stalemate is all the more regrettable because the idea appears to be of profound, even foundational and revolutionary importance. Fortunately, Richard Middleton has published an excruciatingly thorough study, The Liberating Image: The Imago Dei in Genesis 1 (2005; imago Dei is Latin and means image of God). It is far from an easy read, but it provides a brilliant discussion that leaves no stone unturned.

Getting on and off the Wrong Track

Here is what has gone wrong in the interpretation history of the phrase. First, interpreters concluded that the immediate context does not define or explain what the phrase means. Then, they proceeded to do an exhaustive word study of the terms used, which did not yield much to go by either. Finally, they proceeded to think about the phrase in a more philosophical or speculative approach, largely detached from Scripture. Often, this led to a sort of ‘anatomical’ approach: what part of us (of our soul) is the image of God? In the 20th century, Karl Barth famously proposed a relational understanding of the image. His proposal has much going for it (it is a beautiful thought, and God is, after all, a relationship), except that it is not at all clear that this is what the text has in mind. [Note: One could argue that the final line in Genesis 1:27, “male and female he created them”, provides an explanation for the image in the first two lines, as if one were to read “that is, …” However, it is unclear how male and female would be the image of God, considering God is without sex or gender and neither male nor female. Besides, it would logically lead to the conclusion that most animals are created in God’s image as well, seeing they also come as male and female. So more likely, we are to read the third line as a supplement: “And in addition to creating them in his likeness, he also created them as male and female”.]

Middleton succeeds in establishing a strong case for a different original, intended meaning of the image by (a) broadening the literary context to all of Genesis 1 and even beyond; and (b) by considering the historical and cultural context, that is, the world of the ancient Near East. In other words, context leads us to a definition of the phrase after all, if we look just a little bit further.

Middleton argues that the meaning of the image is neither anatomical nor relational but functional and royal. That is, it is not so much what humans are or have or are able to do but what they are commissioned to do: to represent God as king in creation. In Middleton’s (2005: 27) words: “On this reading, the imago Dei designates the royal office or calling of human beings as God’s representatives and agents in the world granted authorised power to share in God’s rule or administration of the earth’s resources and creatures”. With this, Middleton does not propose a new idea, but he makes such a persuasive and comprehensive case that in my estimate, his book convincingly settles the issue.

Clear Hints in Genesis 1

As it turns out, and different from what interpreters have often felt, the immediate context of the phrase is by no means devoid of clues as to its intended meaning. Both in Genesis 1:26 and in 1:28 the image is linked with the idea of having dominion or ruling. And in the broader context of Genesis 1, this is precisely what God does by bringing shape, order, function, and content to the ‘raw material’ of the primordial creation – in one word, by creating. Being made in God’s likeness therefore suggests humans are to do the same.

A functional interpretation of the image finds confirmation in the fact that elsewhere in Genesis 1, God is likewise concerned with assigning function, most obviously when creating the heavenly lights on day 4 to rule (!) the day and the night, an expression of delegated power, not unlike what God does with humanity on day 6.

Middleton goes into much more detail, but the conclusion is clear: that humans are made in God’s image means they represent him and exercise creative power on his behalf.

Confirmation from the Ancient Near East

Broadening the context to the ancient Near East confirms Middleton’s conclusion. It also adds depth and brings out the subversive, countercultural, and revolutionary nature of the concept.

First, in the ancient Near East, a king might place an image of himself in remote parts of the empire to represent his authority. In a sense, we still do this today: an embassy or consulate is likely to display a portrait of its king, queen, or president. As the king of creation, God likewise places an image of himself in the earthly domain – but this is a living image, not a mere statue.

In fact, there may well be a link with the prohibition in the law to make any sort of visual representation of God in the form of an image or statue; after all, God already provided such an image: it is the worshippers themselves.

Second, both in Egypt and in Mesopotamia, the king himself was considered the image and representation of a god on earth, with the express commission to rule and maintain order on earth as the god did in the heavens. This suggests the statement in Genesis 1:27 would have been quite intelligible for the early readers: it would have been understood as ascribing royalty to all humans – not just to the king!

The result is a subtle but devastating critique of what the nations in the world around Israel believed about the order of their world, especially their respective myths of creation. These narratives are unmasked as nothing but a distorting ideology that serves to justify the social system and the king’s absolute power. I already wrote on the subversive nature of the early chapters of Genesis and its critique of creation myths in The Lost World of Genesis 1-11 (2016), but there is more to say.

Subverting the Ideology

Outside of Israel, then, only the king was believed to be in the likeness of the gods. This has far-reaching social and political consequences. Mesopotamia was dominated by city-states. Each city-state was a social system with the king at the top. Such a system needs justification. It is provided by story and myth, first and foremost in the form of the creation myths of the ancient world. Genesis seeks to subvert these myths.

Food for the gods. A common theme in the creation myths of Mesopotamia is that humans were created to relieve the gods of hard labour or, more specifically, to produce food for them. This was the raison d’être for the temple system: it existed to provide the gods with food. Early in the history of Mesopotamia, this put priests into the leading role. Later, kings would often take the lead as the patron of temples. This led to strong royal power and to a society in which much of the land was under direct control of the temple and the king. As a result, many people, perhaps at times even as much as a fourth of the population, were working this land as serfs. Most of the food produced in this system went to temple and palace personnel, of course, not to the gods!

In Genesis 1, nothing suggests God needs or wants anything from what he creates. On the contrary: whereas in ancient myths humans are created to provide the gods with food, in Genesis it is God who provides food for humans (and animals; Gen. 1:29-30)!

Cities and technology. The stories tended to include references to the earliest founding of cities and to the beginnings of various crafts and technologies, such as metalworking and agriculture. These discoveries were believed to be a gift from the gods, leaving humans as passive recipients. As Middleton (2005: 217) puts it:

According to the worldview of Sumero-Akkadian myths, the gods act in history and change the course of human affairs. So do kings, as representatives of the gods on earth. However, the vast majority of the human race was understood to live relatively predetermined lives of mimetic repetition, beholden to their divine and human overlords, reduced to puppets in a social order in which they had no significant agency or freedom.

Major cities traced their origin to a divine act. Babylon, for instance, was founded by Marduk as the centre of the ordered world he created and as the earthly counterpart of his heavenly temple and palace (Babel means Gate of the Gods). Needless to say, such a belief declares city and king to be sacrosanct.

Obviously, Genesis 1-11 includes such stories about beginnings too, but with a twist. The origin of both cities and inventions in Genesis 4 and 10 is human, not divine. We see humans acting in their God-given role, exercising dominion. However, civilisation and invention in Genesis tend to be linked with the abuse of power and therefore with violence in a broad sense of the word. As Middleton points out (2005: 219, 226), this is dominion gone wrong: power is exercised over others, not merely over creation.

Kingship. When it came to the origin of kingship, it was portrayed as a divine institution. A fascinating Mesopotamian document is the Sumerian King List. It lists all the kings that ruled in Sumer (the civilisation that preceded the earliest Assyrian and Babylonian empires) from the beginning of creation. Twice this text states that the kingship descended from heaven, first at the very beginning and then again right after the Flood. How can one argue against what the gods have ordained?

The genealogy in Genesis 5 provides an obvious parallel to the Sumerian King List, but again with an important twist. The people listed are not kings but ‘ordinary’ people. This parallels the application of God’s image to all people rather than merely the king. Noticeably, when Israel finally turned into a monarchy, it was by human initiative and God was not pleased with this move. Obviously, kingship in Israel always had a different status. Middleton (2005: 219) again:

Scripture is also clear that the Torah is not promulgated by the Israelite king (contrast this with the Babylonian Hammurapi). Biblical law (whether in Exodus, Leviticus, or Deuteronomy) is consistently attributed to the mediation of Moses, whereas it is the king’s primary duty to study the Torah and not exalt himself above other Israelites by inordinately increasing his power or wealth (Deuteronomy 17:14-20). This notion of a limited monarchy – limited in historical origin and the duration, limited by the law of YHWH and by prophetic criticism – is radically unique, not just in Mesopotamia, but in the entire ancient Near East. The distinctive application of the notion of imago Dei to the entire human race is thus in profound harmony with the antimonarchical tendency of the prophetic tradition in Israel.

Empire. Again and again, one of the city-states of Mesopotamia would achieve dominance over neighbouring territories and cities. It might even grow into a significant empire (as happened to the Babylonians and the Assyrians). This also needed justification, which was likewise provided by creation myths and other foundational beliefs.

The king was the representative of the gods. As such, he was called to impose the order of, say, Marduk or Ashur on brutal and barbaric nations (the world of chaos) beyond the boundaries of the empire. In this, he paralleled the actions of the gods at the beginning of creation. They, too, had to resist and defeat the forces of chaos and impose order. The motif of such a Chaoskampf (a German term for a violent struggle against personified forces of chaos) is widespread in creation myths.

It is notable that such use of force, violence, and coercion is entirely missing in Genesis 1. Even God’s words of command are loving rather than coercive; one might even wonder if they truly are commands or perhaps almost more like invitations: an invitation to become and to be. It certainly suggests that the kind of rule humans are called to has absolutely nothing in common with tyranny, exploitation, or empire-building.

In short:

The cumulative evidence suggests that the biblical imago Dei refers to the status or office of the human race as God’s authorised stewards, charged with the royal-priestly vocation of representing God’s rule on earth by the exercise of cultural power. Further, I suggested that this interpretation of the image, wherein humanity is granted a share in God’s rule (and thus may be said to be like the divine ruler), underlies the coherent vision of humans as significant historical agents in the primeval history (Genesis 1-11) and may be fruitfully understood as a form of ideological resistance to Mesopotamian traditions that devalued the status and role of humanity. (Middleton 2005: 235)

A Radically Different Social Vision

The result of such convictions “is not simply that the biblical writers had an idea of God that was different from their neighbours (although this is not excluded), but that they had different ideas about what sort of social order was ordained of God, namely, one that nurtured the flourishing of human life, rather than protecting the powerful at the expense of the weak” (Middleton 2005: 195).

One practical outworking of this social vision is that land ownership in Israel was broadly distributed. In Joshua, every male member of every tribe was entitled to an allotment of land. The institution of Jubilee in the law was meant to safeguard this distribution of land. Land should not accumulate in the form of large estates in the hands of a few rich landowners, but every 50th year it should return to the original owning family.

But what about the women? Well, these were very patriarchal times, and things were far from perfect. But we do read about the daughters of Zelophehad in Numbers 27 and 36 (they are also mentioned in Nu. 26:33 and Joshua 17:3).

What is their significance? Why do Zelophehad’s daughters get so much space? They were five sisters whose father had died without leaving a male heir. They had the audacity to stand up in the congregation and address Moses, asking for an allotment of land.

And how does God respond? “The daughters of Zelophehad are right. You shall give them possession of an inheritance among their father’s brothers and transfer the inheritance of their father to them” (Nu. 27:6-7 ESV).

It becomes visible that women had a voice in Israel. Even God listens to them. This has the potential of turning Israel into an unusually egalitarian society. After the conquest, the tribes are left to govern themselves.

Liberté, égalité, fraternité. It took the French well over 3000 years more to come up with the same basic idea, compressed in a beautifully sounding formula. Perhaps it is better not to reduce it to a political and ideological formula (which is too easily abused), but the underlying idea is thoroughly biblical.

Every person is made in God’s image and therefore called to exercise royal authority – but not by violence or dominating others.

No wonder Middleton called his book The Liberating Image!

Attribution

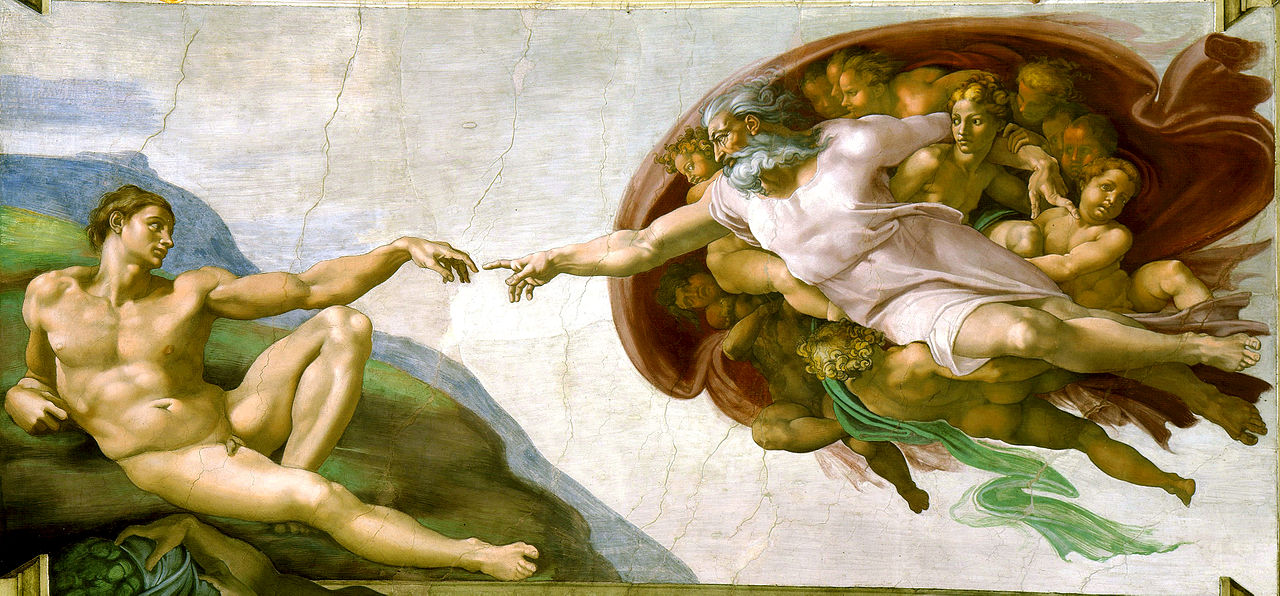

Michelangelo. Ca. 1511. “The Creation of Adam” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Creaci%C3%B3n_de_Ad%C3%A1m.jpg> [Accessed 30 April 2020] Public Domain

FDRMRZUSA. 13 September 2018. “Mesopotamia c. 1200 BC” <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mesopotamia_1200_BC.jpg> CC BY-SA 4.0

Dries Augustyns <https://unsplash.com/photos/xn1aRfVNY1w> CC0

Falco <https://pixabay.com/photos/avignon-france-provence-1603343/> CC0

References

All Bible quotations from: The Holy Bible: English Standard Version. 2001 (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles)

Middleton, J. Richard. 2005. The Liberating Image: The Imago Dei in Genesis 1 (Grand Rapids: Brazos Press)

Disclosure of Material Connection: Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission. If you purchase anything through such a link, you help me cover the cost of Create a Learning Site.