To summarize the message of the prophets in two words – is that possible? I think so. It takes two short Hebrew words, one of which I am sure you know. It also needs an additional concept. And, okay, maybe a third word. But then we capture the heart of the matter.

You can also watch this content as a VIDEO PODCAST or listen to it as an AUDIO PODCAST

Such considerations make sense because many Bible readers quickly lose their way in the forest of biblical prophecies. The question arises: How can we help Bible readers to read the prophets with more understanding?

Recently I was asked to give an introduction to the prophetic books in just over an hour. I tried to do this by addressing three aspects: the role of the prophets, their time, and their message (as I said, two words and a concept).

I am sharing my draft here in case you need to do something similar sometime; maybe it helps.

The Role of the Prophets

I often approach the subject of the prophets in the following way. I first ask what the audience associates with the idea of a prophet; what comes to mind? When I have collected enough answers, my next question is: What of all this is essential?

It is usually possible to work out that the prophets were spokespersons or messengers of God; they conveyed his words and concerns.

I follow up with two further questions. First, who was the first prophet in Israel? The answer is Moses. In Deuteronomy 18:15-18, Moses refers to himself as a prophet. And in this passage, he announces further prophets whom God will “raise up”.

This leads to the second question: How many prophets do you think there were (say, between Moses and the exile)? The answer is difficult for many. There were more than most people think. There must have been at least several thousand.

After all, we are talking about 700 or 800 years, depending on the dating of the Exodus. There were always prophets during this time. Especially in Kings and Chronicles, prophets are regularly mentioned; about most of them, we know very little. In some passages of Scripture, it becomes evident that there were larger groups of prophets at the time in question.

In 1 Samuel 10:5, 10 and 1 Samuel 19:18-24, Saul encounters a group of prophets. Both times, he is overwhelmed by the presence of the Spirit in their midst. In 1 Kings 18, it is reported that Queen Jezebel is killing the prophets of the Lord, but that a certain Obadiah, who was over the king’s household, hid and cared for 100 of these prophets. In the stories about Elijah and Elisha, there is repeated mention of – so literally – “the sons of the prophets”, some of whom live in community. These sons of the prophets are sometimes understood as disciples of the prophets or even as a school of prophets. However, it is more likely that they are simply members of the prophetic community (compare ‘sons of Israel’ or ‘daughters of Jerusalem’). This would mean that in the Northern Kingdom, at least at the time of Elijah and Elisha, hundreds of prophets were active at the same time. Therefore, in eight centuries, there must have been thousands of prophets.

In other words, the prophets formed a movement – one that was essential for Israel. The prophets were uncompromising in their commitment to the God of Israel. They kept the faith of Israel alive. Renewal often came through them. It is hard to imagine how Israel’s faith would have survived the exile without them and their words.

At this point, one more question needs to be asked: How many prophetic books are there in the OT? There are only 16. Which means: These books are only the tip of the iceberg. For the vast majority of the prophets, none of their words has been handed down. Only in the final phase, from about 150 years before the exile, were the words of individual prophets collected and handed down in writing. Why?

The relationship between Israel and God had fallen into a deep crisis. It was at risk of collapse. It must have been increasingly clear that harsh consequences would follow. For this reason, the emphasis of the prophetic message shifts somewhat towards warning and confrontation. And, in view of the coming exile, it must have seemed wise to put the message in writing so that it would not be lost.

The prophets were not only God’s mouthpiece. In this phase, a second role emerged. They increasingly appeared in the role of the accuser or prosecutor. There was a trial. The covenant, a formal agreement between God and the people, was not being kept. There was a breach of contract – and the prophets brought charges. This explains why, for example, in Isaiah 1:2 and Micah 6:1-5, heaven and earth, hills and mountains are called upon as witnesses: They are expected to confirm the breaking of the covenant.

The Time of the Prophets

The role of the prophet is thus that of spokesman and prosecutor. The resulting indictment and verdict can only be understood against the background of their time and the events of that time. Several prophetic books are explicitly anchored historically in their first verse; see, for example, Isaiah 1:1. What the prophets say and write is historically conditioned.

I keep this second section brief; I will not attempt to set out the history of the OT here. A simple timeline, as shown here, can help to give an overview.

The relationship crisis led to a double existential crisis (the arrows in the picture). For Isaiah and his contemporaries (Micah, Hosea, Amos, Jonah) the Assyrians brought this crisis about. Isaiah witnessed the end of Samaria and the Northern Kingdom (722 BC) and the invasion of Judah by Sennacherib (701 BC). For Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Habakkuk, and Zephaniah it was the Babylonians; in 586 BC they destroyed Jerusalem and the temple.

As foretold in the book of Isaiah (Is. 40-48), the Persian king Cyrus ended Babylon’s world domination in 539 BC. He ordered the rebuilding of Jerusalem and its temple. This was followed by a time of return and restoration for Israel, accompanied by the prophets Zechariah, Haggai, and Malachi. In addition, Isaiah and Daniel also spoke of this time and far beyond.

The Message of the Prophets

This brings us to the message of the prophets. It can be summed up in two Hebrew words:

1. The first word is shuv, a simple verb much used in the OT. In the context of the prophets, it is often translated as repent, but this is an unclear and abstract word. What does it mean to repent? How does one do this? The better translation is to turn – a concrete and visual term. The action has two sides: One turns away (from idols and injustice) and one turns towards God and righteousness. Repentance is the goal of the prophets.

2. The second word is shalom. It sums up what God’s future looks like: restoration, peace, healing, justice, etc. In Isaiah, the theme takes up almost half the book. Shalom is the goal of God and functions as a motivation for repentance.

3. Perhaps a third word is needed: justice. Shalom is God’s contribution; righteousness is what God expects from Israel (so Dt. 16:20; cf. Is. 5:7).

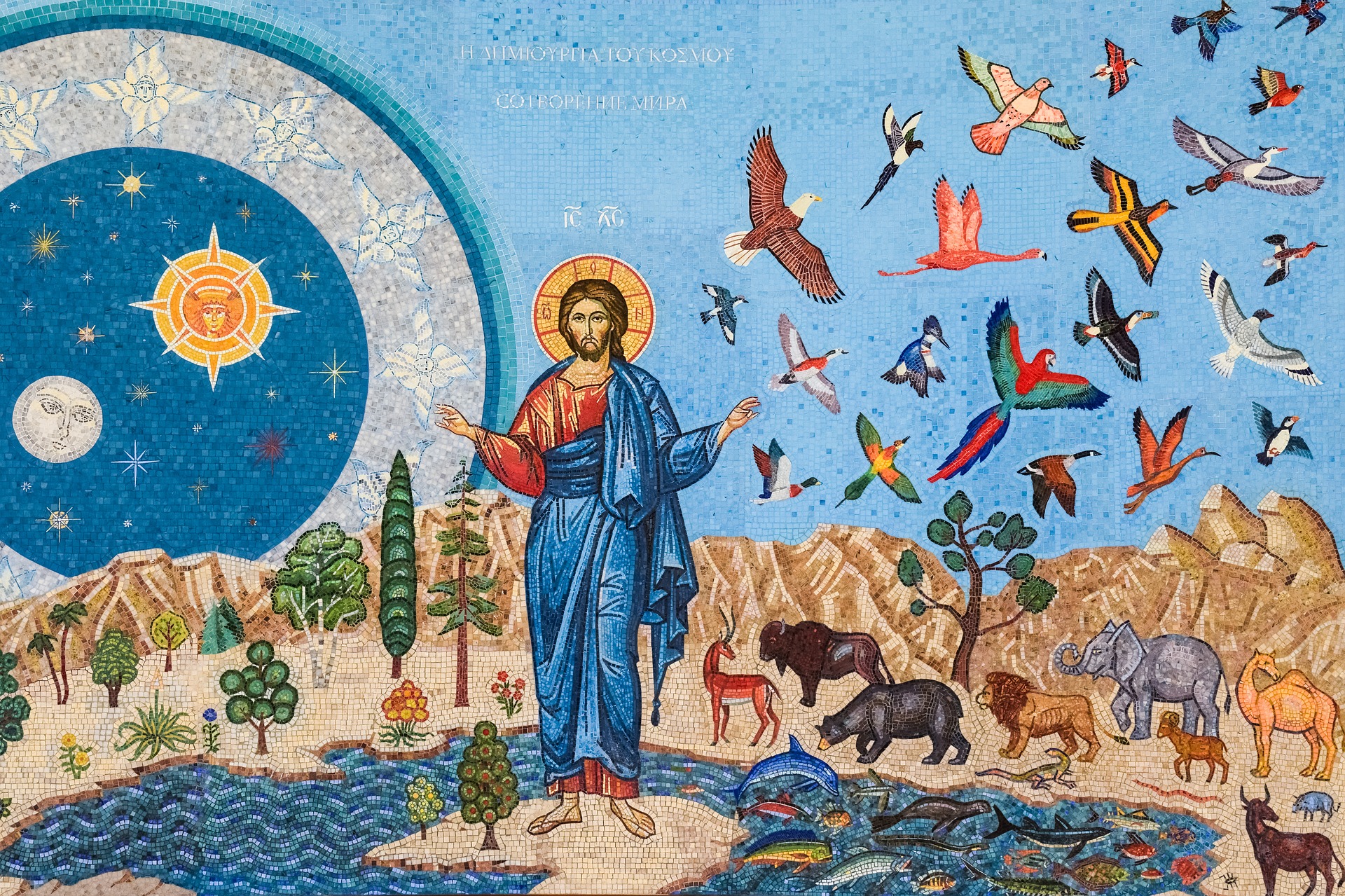

4. In addition, we need an idea that appears again and again in the prophets: the day of the Lord (see picture). It stands for the intervention of God in history. The day has two sides. It is about judgment but also about restoration: the coming time of salvation made possible by the day of the Lord. The condition for participation in the restoration is the first word: shuv.

Now it gets a little more complicated. For the picture is simple, but the fulfilment is not. There is not just one day of the Lord. The plague of locusts in Joel (date unknown), the destruction of Jerusalem (586 BC) and the end of the Babylonian empire (539 BC) are all referred to as the day of the Lord.

In part, then, for the prophets, the day of the Lord is in the near future; for us, it is in the past. But in part it is about the distant future, the end, and the new world order that God will then establish. It becomes complicated above all because the prophets often mix these two, near and far, historical and final. We call this foreshortening. It is as if they do not perceive the time dimension or simply ignore it: Everything seems to happen simultaneously, within a short time period.

We find a good example of foreshortening in the second half of Isaiah. Here we read about Cyrus and the end of the exile, followed by the return and the rebuilding of the temple. But there is also the suffering servant (Is. 53), a prophetic image that finds its fulfilment in Jesus. Beyond that, Isaiah talks about everything else God has in store: glory and shalom, even new heavens and a new earth. One would not guess that there are more than 500 years between Cyrus and the servant. Between the servant and the consummation, there are at least another 2000 years.

At this point, it gets even more complicated because we are living in the time of fulfilment. The future is no longer just future; it has already begun. Jesus says to his disciples after the resurrection: Peace (shalom) be with you (John 20:19). The new creation already exists (2 Cor. 5:16; Gal. 6:15). And the eternal joy that follows salvation is also not only future (Is. 35:10; cf. Jn. 16:24; 17:23).

This makes the message of the prophets relevant for today. Conversion, turning to God, is still called for. It leads those who respond into the experience of salvation and glory announced by the prophets:

Concerning this salvation, the prophets who prophesied about the grace that was to be yours searched and inquired carefully, inquiring what person or time the Spirit of Christ in them was indicating when he predicted the sufferings of Christ and the subsequent glories. It was revealed to them that they were serving not themselves but you, in the things that have now been announced to you through those who preached the good news to you by the Holy Spirit sent from heaven, things into which angels long to look. (1 Pet. 1:10-12 ESV; emphasis added)

Attribution

Dimitrisvetsikas1969 <https://pixabay.com/photos/genesis-mosaic-iconography-2435989/> CC0

Other illustrations are mine; CC0

References

All Bible quotations from: The Holy Bible: English Standard Version. 2001 (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles)